Protests have multiplied around the world following the videotaped murder of George Floyd by a police officer on 30 May 2020. That video was published after a series of killings of African Americans were widely shared on social media, including the ones of Breonna Taylor shot and killed in her own house and the lynching of Ahmaud Arbery while he was jogging. This comes against a backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has resulted in a rising number of hate crimes and discrimination towards racial minorities. The pandemic has disproportionately affected and killed Black and Latinx communities in the United States—and Black and racialized minorities beyond—laying bare systemic inequalities.

Social media platforms have played a significant role in the current awakening, acting as a channel for numerous online campaigns, petitions, and viral hashtags. The renewed focus on the Black Lives Matter movement has also triggered statements of numerous businesses that publicly aligned themselves with the movement. Those declarations of support bring necessary attention to the origin and transformation of corporate accountability.

The Sullivan Principles in the fight against institutionalized racism

One of the first Business & Human Rights (BHR) frameworks was elaborated in 1977 by Reverend Leon Sullivan. Through a code of conduct called the Sullivan principles, the African American clergyman and board member of General Motors urged US businesses operating in Apartheid South Africa to increase “the number of blacks and other nonwhites in management and supervisory positions.” But with no monitoring mechanism and geopolitical concerns, the Sullivan principles had a limited practical impact.

However, in 1999, then UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, proposed to relaunch them into the Global Sullivan Principles of Social Responsibility while founding the Global Compact, inviting businesses worldwide to comply with human rights. Under these principles, businesses ought to encourage “racial and gender diversity on decision-making committees and boards.”

Businesses should not only avoid causing or contributing to human rights abuses, they should also seek to prevent or mitigate those.

Since then, companies have increasingly acknowledged the relevance of soft human rights instruments. Since the Human Rights Council endorsed the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights in 2011 (the “UNGPs”), the have remained the authoritative international standard on corporate responsibility. The UNGPs sought to implement the “Protect, Respect and Remedy” Framework developed by John Ruggie in 2008.

The UNGPs provide that states must protect human rights (Principle 1) while companies should only respect them (Principle 11). Respect entails both negative and positive actions. Businesses should not only avoid causing or contributing to human rights abuses, they should also seek to prevent or mitigate those. To do so, they can conduct due diligence procedures identifying and assessing actual or potential adverse human rights impact by relying on internal or independent expertise. They should also track the effectiveness of their response and consult with relevant stakeholders, paying particular attention to marginalized and vulnerable groups (Principle 20).

Away from its origins, the BHR framework seems to have developed a focus on corporate operations rather than corporate governance.

The structural aspect of the responsibility to respect

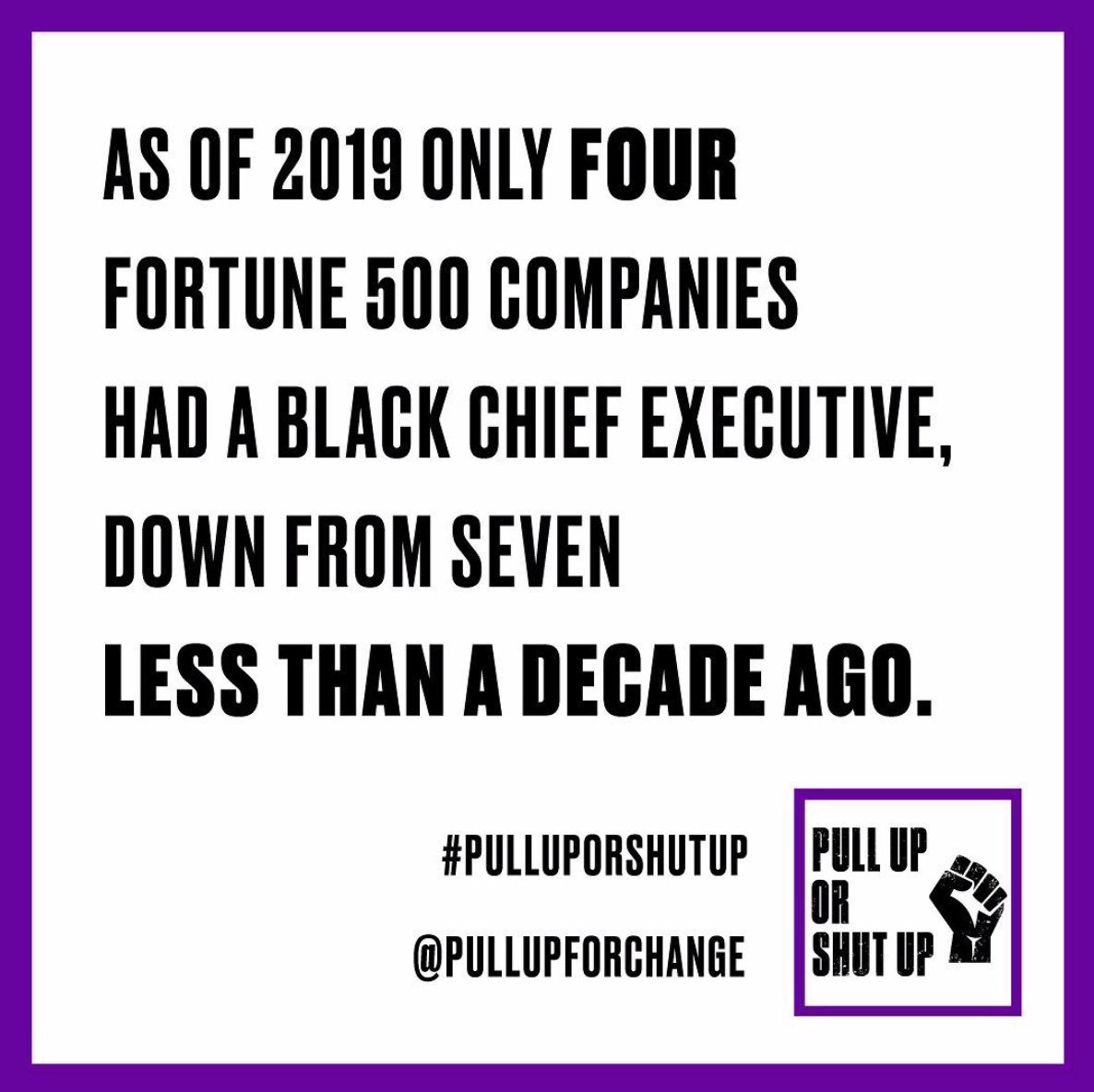

Reacting to the multiple declarations of solidarity by businesses, Sharon Chuter, Founder and CEO of UOMA Beauty initiated the movement Pull Up for Change and a call to action #pulluporshutup on 4 June 2020. She thereby asked brands “who have released a statement of support, to publicly release within the next 72 hours the number of Black employees they have in their organizations” at the corporate and executive level.

To date, the page counts 114,000 followers, and 100 companies (from small companies to big groups) have voluntarily disclosed the requested figures. Against a US benchmark of 10% Black graduates nationwide, 64 of participating companies count less than 10% Black people in leadership roles. Companies under the benchmark issued various policy statements. Among them, Adidas—which has relied heavily on Black culture for marketing purposes—declared that “a minimum of 30% of all new positions in the US will be filled with Black and Latinx people” while Nike, with similar marketing strategies, has not yet issued an action plan. In addition, the campaign Fifteen percent pledge called on major retailers to distribute 15% of Black-owned businesses products on their shelves. Major retailer Sephora has already joined the pledge.

Image by @pullupforchange.

According to the International Labor Organization (ILO): “practices that have the effect of placing certain individuals in a position of subordination or disadvantage” in the workplace because of their race constitutes discrimination in employment. The current movement offers a structural reading grid of the UNGPs as a company may comply with human rights in the conduct of its operations but should further be structured in compliance with the principle of non-discrimination. Corporate governance becomes an element of compliance, beyond the requirements of corporate law.

What happens throughout the supply chain

As business can hardly be done without resorting to an elaborate supply chain, businesses should respect human rights not only in their own activities but also as a result of their business relationships (Principle 18). In that process, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) states that special attention should be paid to people who are at risk of vulnerability or marginalization.

Yet businesses participating to the UN Global Compact rank the control of their supply chains as one of their biggest challenges due to their complexity.

In that context, a structural interpretation of the responsibility to respect is all more relevant. From a business perspective, one of the top factors to prioritize due diligence throughout the supply chain is the reputational risk. From a legal perspective, regardless of whether states protect human rights or not, businesses still ought to respect them, wherever they operate.

Structural control of business partners that lack a representative workforce or operate in states that apply systemic discrimination against minorities would be particularly relevant.

Businesses promoting human rights: the new normal?

Beyond the baseline responsibility to respect human rights, the OHCHR recommends businesses to set a higher standard and promote them. The ILO also supports that employers should promote equality of opportunity at all stages of recruitment.

Traditionally applicable to States and UN agencies, the action of promoting human rights entails the adoption of a goal, a process and an outcome.

Against a US benchmark of 10% Black graduates nationwide, 64 of participating companies count less than 10% Black people in leadership roles.

The urgency and speed of social media campaigns and the accrued interest they raise seem to de facto urge businesses to not only respect human rights but also take a proactive stance and promote them. This is particularly true for businesses that are especially sensitive to reputational risks, as corporate statements on social media are now under scrutiny. The potential backlash was illustrated by the insensitive tweet of CrossFit’s CEO, which resulted in the end of its partnership with Reebok and other affiliations.

Overall, following their statements, businesses’ actions have varied. Some have created grants, while others have donated to social justice and anti-racist organizations. Mary Barra, CEO of General Motors, pledged to create an inclusion advisory board within the company.

What’s next?

While the UNGPs have sometimes been criticized for their lack of enforcement mechanisms and normativity, activism through social media platforms is certainly strengthening the “web of corporate accountability.” Corporate governance and structural responsibility are worth bringing to the table of current discussions on the legally binding instrument under the auspices of the Human Rights council. After all, online campaigns increase customers’ scrutiny to corporate conduct and are an effective tool to empower this bottom-up lever of accountability.