Jagadeesh MV/EFE/EPA

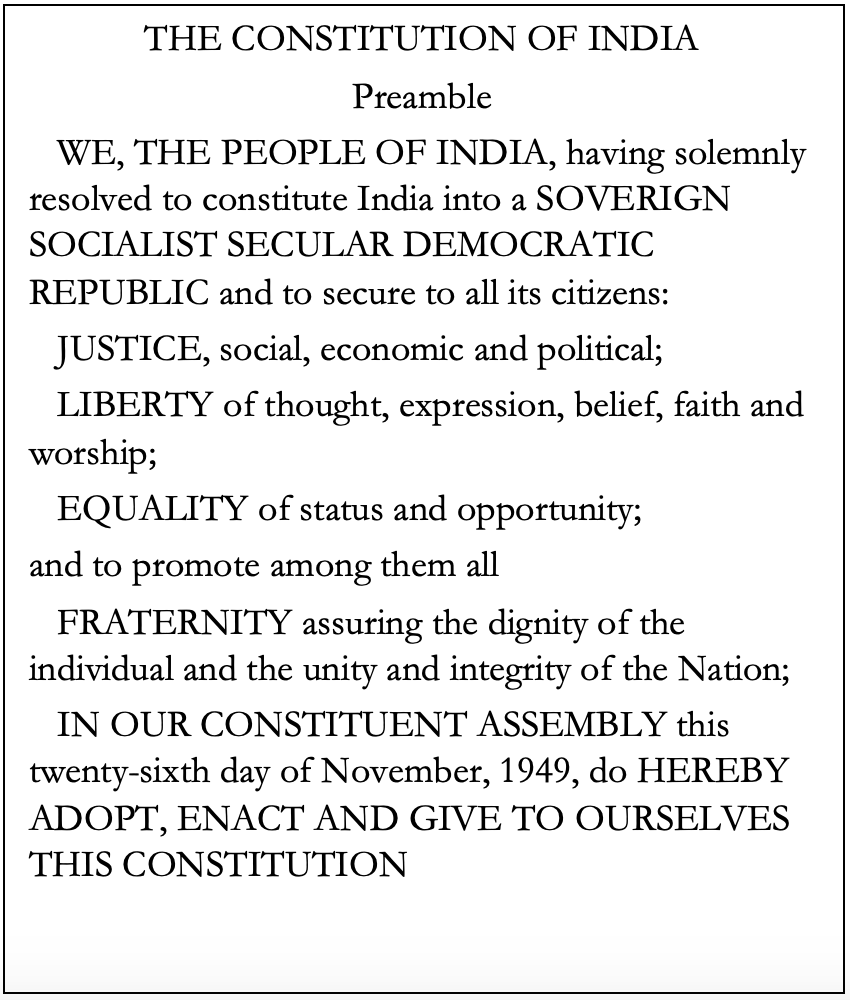

On the second day of student-led protests across India, it was a sunny afternoon in Bangalore. I ventured to the town hall, a traditional site of protest in Bangalore, with the constitution in one hand and Ambedkar’s Annihilation of Caste in the other—a seminal book written by the chief architect of India’s constitution that unpacks the relationship between caste, Indian society, and rights. As I entered the area, I was stopped by the police stating that permission to protest had been denied. But this did not deter the protestors; instead, a silent march took place from the centre of the city to Freedom Park, where protests are often held. As I walked with the protestors, I felt the urgency of the youth leaders, all of us motivated by the preamble of India’s constitution:

Demonstrators across the country were protesting India’s Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019 (CAA), which for the first time in India’s democratic history relates the idea of citizenship with a particular religion. Specifically, this Act excludes Muslims from obtaining citizenship if they entered India on or before 31st December 2014 from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan. Conversely, specific faiths are listed for an accelerated process of citizenship: Hindu, Sikh, Zoroastrian, Buddhist and Christian migrants from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan. But the issue gets murkier when read along with the mechanism for implementation, the National Register of Citizens (NRC), where Indians will be asked for proof of citizenship. As the protests gained momentum, India’s home minister backtracked on the NRC and decided to use the existing process of the National Population Register, a database of residents in India that includes foreigners who have been residing in India for six months or more. The first time an NPR was prepared was in 2010, under the provisions of the Citizenship Act (1955), but the Home Minister has insisted on undertaking the process again in 2020. The NPR is seen by activists as the base document for the preparation of the NRC.

India’s preamble identifies India as a sovereign, socialist, secular, democratic republic, and this new test of citizenship directly contradicts the spirit of the preamble. The battle is ongoing, and while much has been written about the unconstitutional nature of the CAA, NRC and NPR, I will argue that the test for citizenship fundamentally changes the relationship between Indian citizens and the state, thereby hollowing out the spirit of the preamble. Nonetheless, the protests offer a beacon of hope in reviving the spirit of India’s constitution.

The Citizenship Test

Who is an Indian citizen? This is the fundamental question that guides the efforts behind the CAA, NRC and NPR. India’s history is a history of secularism and a narrative of a confluence of diversity. But as India became independent, it was also partitioned—which is the last time this question of citizenship was posed. And at that time, the process of answering this question rendered millions homeless and divided populations on religious lines.

Asking this question again now, and explicitly excluding Muslims, forces one to think of the destructive history of partition. The Modi regime has constructed a national identity that is informed by the need for Hindu supremacy. Hindutva—which is the ideological basis of the Rashtriya Swayam Sewak Sangh, a cultural organization, and its political arm, the Bharatiya Janata Party—shapes their policies and attitudes towards citizenship.

Indeed, there has been a rise in hate crimes against Muslims since the Modi regime came into power. A particular hate crime has been mob lynching because of the cattle trade or consumption of beef, as Hindus see cows as a sacred symbol of life to be protected. Cow vigilantes openly roam the streets to police those who are seen carrying or consuming cattle. Marginalized communities like Dalits and Muslims are most affected by such an aggressive practice of bovine politics, but this is only a symptom of the larger question of who belongs to India and who does not.

The preamble has gone from words in the constitution to a resounding protest anthem.

Polarisation within India in the Modi regime has always been about citizenship not in the purely legal sense but as a sense of belonging. Examples are visible in the myriad of terms used to describe those in the margins, like “Urban Naxal” (a mysterious label attached to many intellectuals that challenge the regime, which originated in a book written by Vivek Aghnihotri) and “Tukde-Tukde gang” (the “gang that breaks India”, which was used to target students of the Jawaharlal Nehru University). The reason for their exclusion has been their inability to fit into the rigid frame of belonging that the Modi regime has in place, which is built on the foundation of Hindu supremacy with no tolerance for dissent.

The CAA, NRC, and NPR are embedded in this construction of nationalism. The Citizenship Rules of 2003, under which the NPR is being prepared, contain a provision for “doubtful citizenship”. This means that any “doubtful citizen” can be ordered to submit documents to prove his or her citizenship. It is in opposition to this exclusionary frame of belonging that the spirit of the Preamble stands strong.

Reviving the Spirit of the Preamble

The collective reading of the Preamble has now become a deliberate ceremony of reclaiming the founding values of this Nation, one that is inclusive and not discriminatory. As the Preamble is being read, it is coupled with slogans of inclusion and dissent against the Hindutva foundation of the Modi-Shah regime. As a piece by Rohit De and Surabhi Ranganathan argues, the constitution is laying the foundation for the rediscovery of the Indian republic and strengthening federalism as states or sub-national units are rebelling against this law. The legislative assembly in Kerala, for example, has already passed a resolution opposing the implementation of the CAA in Kerala.

This is a significant moment in India’s constitutional interpretation as it is not the courts that are doing the interpretation, but the people themselves. In a conversation with a young student protesting in Bangalore, I asked what the constitution meant to her and she said:

“The constitution is not just a founding document but a living one. Let me just say this, it is a document that is an agreement between the citizens and the state. The state is violating its terms by not adhering to the preamble and secularism. We have to take to the streets as citizens to make the state understand that we are now in disagreement.”

The preamble has gone from words in the constitution to a resounding protest anthem. The protestors and many Indians refuse to subscribe to this citizenship test and have vowed not to show their documents, as the poem by Varun Grover narrates in Hindi: “We will not show you our documents.”

In India, hope has come in the form of young students armed with the constitution rebelling against the citizenship test. Their jurisprudence and constitutional interpretation emerge from pluralism and inclusion that seeks to expand the rigid framework of belonging that the Modi regime has put in place.

It is in this street jurisprudence of hope and inclusion that India can reclaim the words and tenets of its preamble. With the massive lockdown presently underway in India due to the COVID- 19 pandemic many protests have been cancelled, and in a strange twist of events the exercise of the national population register is indefinitely postponed. Whether this marks the Modi-Shah government retracting from its move is as yet unknown