The International Human Rights Funders Group and Foundation Center recently published Advancing Human Rights: Update on Global Foundation Grantmaking, a report analyzing the who, what, where, and how of human rights philanthropy. The latest update gives us an increasingly robust data set on human rights grantmaking around the world. While it provides our colleagues in the human rights philanthropy and NGO communities a snapshot of where money is being spent, a natural follow-up question looms: could academics use this data set in their research? Researchers are always on the lookout for new sources of data, right?

The International Human Rights Funders Group and Foundation Center recently published Advancing Human Rights: Update on Global Foundation Grantmaking, a report analyzing the who, what, where, and how of human rights philanthropy. The latest update gives us an increasingly robust data set on human rights grantmaking around the world. While it provides our colleagues in the human rights philanthropy and NGO communities a snapshot of where money is being spent, a natural follow-up question looms: could academics use this data set in their research? Researchers are always on the lookout for new sources of data, right?

This question of bridging the divide between philanthropy practice and scholarship is less simple than it might appear.

This question of bridging the divide between philanthropy practice and scholarship is less simple than it might appear. As someone who worked for over a decade as a foundation program officer before pursuing a PhD in political science, I’ve found that the questions I would ask as a practitioner differ greatly from those I ask as a researcher and scholar. While my goal as a program officer has always been to promote accountability and democracy, I’ve had to acquire a more detached objectivity as a researcher and ask questions with a broader perspective. I helped to provide some of the early data to the Advancing Human Rights initiative within my foundation, and looking at it now as a researcher provides a different view.

As a practitioner, I’ve always been impressed with the massive data coding effort that Advancing Human Rights entails. Examining each grant to determine which region, issue, population and strategy it addresses, and then to assure there is no double-counting of grants, is no small feat. From my own experiences trying to cull information from foundation grant databases, I know it is an immensely time consuming effort and one that often leads to further questions and can yield multiple interpretations. This report is part of a larger trend towards greater transparency in the philanthropic sector, and one that should be commended. Academics have already taken advantage of the increasing information available online.

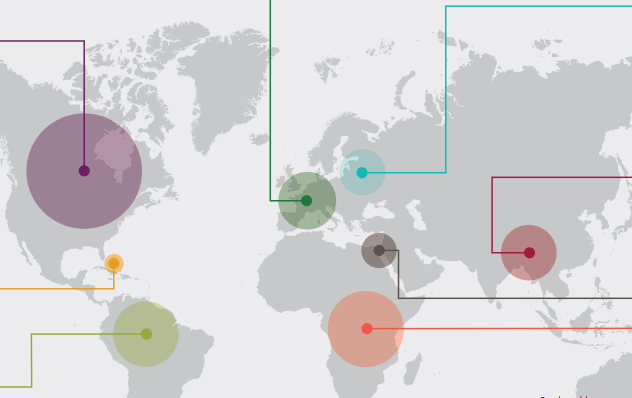

IHRFG (All rights reserved)

"While we agree as practitioners on a certain set of priorities and definitions for human rights and other key terms, to outsiders they may seem limiting."

Lucy Bernholz and Sarah Reckhow have recently discussed a number of reasons why academics could find Advancing Human Rights useful—or why not. Their suggestions are instructive. First, the primary audience is those who study human rights philanthropy specifically. For these scholars, the data set provides a snapshot of human rights grantmaking around the world, the important grantors and grantees, and which regions, issues, populations and strategies attract the most funding. It allows researchers to “follow the money” (quoting Sarah Reckhow) without having to delve into individual organizations’ financial reports. This data set can also provide new perspectives for practitioners; Melinda Fine’s recent blog, for example, examines some surprising new trends from the most recent edition.

However, the report also leaves some gaps. What was not funded and why? For further information on the motivations behind funding decisions, researchers can read between the lines of program strategies, or dig into archives to search out strategy memos and grant recommendations. The Rockefeller Archive Center in Pocantico, New York, is a frequent stop for philanthropy scholars, and the Open Society Archives in Budapest and the new home of the Atlantic Philanthropies’ archives at Cornell University may become important resources as well. As a researcher, I urge all funders to capture their institutional memory and make it accessible to future scholars.

For those studying the NGO sector in various regions (my own research included), the self-reported data shared in Advancing Human Rights only provides part of the story. It shows which NGOs are well connected internationally and perhaps maintain a high level of professional management in order to receive and administer funds. NGOs or less formal civil society groups that subsist on smaller individual donations, in-kind funding, volunteer labor, domestic government funding, corporate philanthropy, or the growing number of community foundations may not be included in this report. As closing space for civil society makes international funding more difficult to report openly, physically send, or accept (as organizations increasingly refuse it in order to safeguard their credibility in the domestic context), important sections of the human rights NGO community may be left out of this data set.

Finally, while we agree as practitioners on a certain set of priorities and definitions for human rights and other key terms, to outsiders they may seem limiting. I once had a Lithuanian colleague from a partner organization ask why we didn’t fund political parties. Another foundation staff member and I rejected such an idea out of hand and explained how we were barred under US foundation law from being involved in partisan politics. However, it stayed with me that, for my colleague, funding political parties was a logical extension of the work we were doing already and a natural fit. Where do political parties, labor unions and religious institutions, as vital members of a plural and civil society, stand in the disbursement of international resources on human rights? Many European political parties maintain operational foundations that work on human rights issues around the world, as well as the Westminster Foundation for Democracy, International Republican Institute and the National Democratic Institute. As for labor unions, the Solidarity Center is affiliated with the AFL-CIO (American Federation of Labor & Congress of Industrial Organizations) to promote workers’ rights worldwide, and it also works alongside the National Endowment for Democracy, whose grantmaking is included in the Advancing Human Rights research.

Another example of a challenge of priorities—one which feels particularly relevant in light of Trump’s election in the US, the Brexit vote in the UK, and the rise of right-wing populism across Europe—is that our focus on minority populations as the most marginalized sectors of society may have missed those who feel marginalized or without equal access to opportunity within the majority population. Certainly, 2016 has taught us that the lack of economic and social mobility of all citizens can be a potent force in electoral outcomes, and, by extension, a potential hindrance in the future of legislated human rights protections.

Having outlined the above limitations of Advancing Human Rights, I am once again of two minds. As a researcher, I recognize these limitations as valid critiques, but as a practitioner, I don’t know what the alternative would be. How would the authors operationalize a different set of choices? How can research balance transparency with the inherent security concerns? How can one devise definitions that are narrow enough to code data but broad enough to include important human rights work outside of our funding priorities? At its core, the Advancing Human Rights research is the field’s only source of qualitative and quantitative data on human rights funding. It is important, however, to periodically discuss and openly debate the scholarly critiques and acknowledge the limitations.

***A version of this piece was originally published on the IHRFG blog in March 2017.