Prachatai/Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

In teaching business and human rights (BHR), I try to get my students excited about this fast-moving field, which offers more promise of changing conditions for ordinary people than other areas of human rights activism. At the same time, they need to remain clear-eyed about the problems that make it hard to push businesses beyond the ingrained ways in which they operate.

Business and human rights is not just about “doing well by doing good” as the corporate social responsibility (CSR) movement has it, nor is it captured by the win-win proposition of “shared value.” Rather, it is a call to tackle the growing concentration of corporate power, the outsized political influence of capital , the entrenched primacy of the profit motive for boards and managers, and the norm of shielding parent companies from the human rights impacts of their subsidiaries. It seeks to overcome the obstacles to obtaining remedy for human rights violations.

I taught my first business and human rights course in July 2008, a few weeks after John Ruggie formally presented the “Protect, Respect, Remedy” Framework to the UN Human Rights Council—the framework that underpins the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), which the Council unanimously endorsed three years later. The UNGPs mandate that companies conduct human rights due diligence and provide redress when harms occur; that governments have a duty to make sure companies do so; and that companies must meet their “responsibility to respect” regardless of whether states meet their “duty to protect.”

The BHR movement has leveraged the UNGPs to promote substantial progress. Some companies have buckled under pressure to adopt a company-wide human rights policy, while others have declared zero tolerance for land grabs. Companies are signing up for multi-stakeholder initiatives that target specific problems; and some have made visible efforts to right the bad practices of business partners. Governments are also acting: Germany’s legislature is deliberating a new due diligence law, and Thailand is the latest global South country to launch a National Action Plan on business and human rights. Some developments are promising but ambiguous, such as the Business Roundtable announcement last year that they will no longer emphasize maximizing shareholder returns; and sometimes the effect is hard to measure, such as with employee activism. There are also great leaps forward, such as the landmark ruling by the UK Supreme Court in Lungowe v Vedanta Resources, which opened the door to parent companies being held liable for the human rights impacts of its subsidiaries.

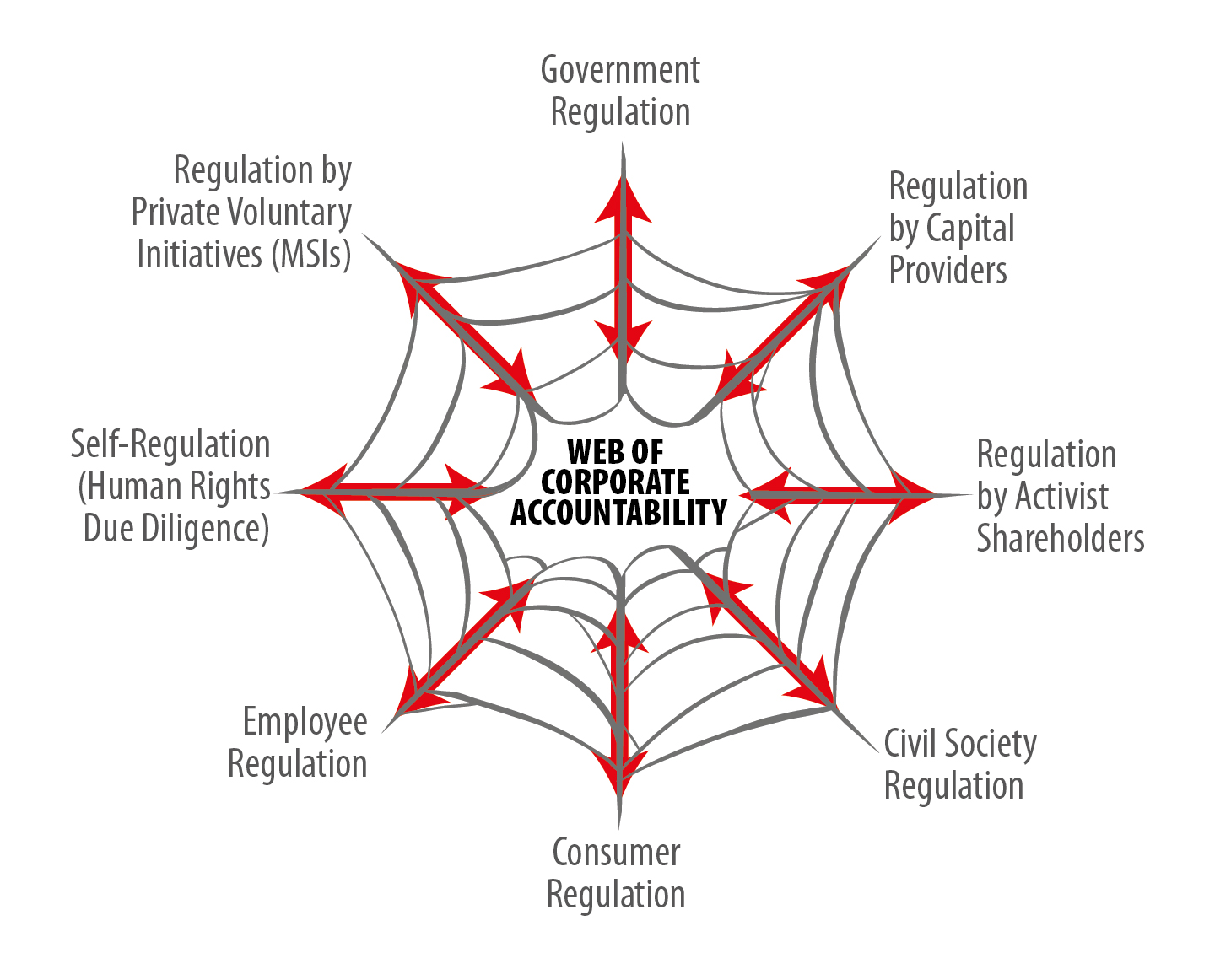

Just as the spider builds its web, the diverse actors that comprise the business and human rights movement steadily build the web of corporate accountability.

Yet progress can feel like an illusion. Highly profitable companies like Apple are avoiding paying taxes, food conglomerates are buying from cattle ranchers who are clearcutting Indonesian rainforests and setting the Amazon on fire, and human rights defenders continue to be killed when peacefully protesting harmful mining, agriculture and hydro projects.

To conceptualize the complex vectors along which society can act to make corporations accountable for their human rights impacts, I have developed a visual, which I call the “Web of Corporate Accountability.” It illustrates that government, through law and policy, is just one actor holding corporations to account; civil society, consumers, investors, and other actors play key roles in both holding companies to account and pushing them to self-regulate—often in an effort to stave off government regulation.

The radial lines of the web represent levers by which society “regulates” corporate conduct:

- Government Regulation—the UNGPs’ “first pillar,” the state duty to protect;

- Self-Regulation, through human rights due diligence;

- Regulation by Private Voluntary Initiatives, a hybrid form of governance where multi-stakeholder initiatives sit;

- Regulation by Capital Providers, that is, debt and equity investors;

- Civil Society Regulation, representing civil society campaigns, boycotts, and the development of benchmarks and ratings;

- Consumer Regulation, through individual consumer behavior. This radial has been a relatively weak force for accountability compared to expectations.;

- Shareholder Activist Regulation, a hybrid form of investor regulation and civil society activism, where socially conscious shareholders (including individuals) try to change corporate conduct by filing and voting on shareholder resolutions;

- Employee Regulation, the newest radial that my 2019 class added following action by employees at Google, Amazon, Microsoft, Facebook, and Wayfair over issues ranging from complicity in the Trump administration’s mistreatment of immigrants to inaction on climate change.

Just as the spider builds its web, the diverse actors that comprise the business and human rights movement steadily build the web of corporate accountability—with some radials reflecting more activity at certain points in time, while other radials lie dormant for a while. And, as in the case of Employee Regulation, some new, surprising radials emerge. The dynamism of the business and human rights landscape is also evident in the shifting of locus of activity from one radial to the other, with the web being more tightly woven as more opportunities for corporate accountability are revealed.

The web concept captures the interactions between various actors working across radials, hence the double-headed arrows cutting across the center of the web. Such interactions occur, for example when: NGOs prevail upon senators to send letters to investors about deforestation; socially conscious shareholders file resolutions against BlackRock for not pushing its portfolio companies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions; Amazon employees file a shareholder resolution; or social movements successfully lobby government to rein in companies. Each actor influences, or has the ability to influence, every other actor.

Under pressure of their customers and sometimes their employees, companies sometimes try to influence government to improve its own human rights record, as when several in the tech sector stood up to the Trump Administration over what are widely deemed to be discriminatory immigration policies. That pressure represents today’s social expectation that to be responsible companies must speak out in the face of human rights violations. Companies enlist consumers in virtue signaling campaigns that affect human rights, such as the Nike campaign in support of former NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick, when he was black-listed for kneeling at the national anthem in protest of police brutality and racism towards black Americans.

The visual also illustrates the “polycentric” approach to governance and accountability, that Ruggie envisioned. It can guide the development of multi-pronged advocacy strategies across radials to compel companies to respect human rights. The persistent holes in the web, on the other hand, are the reality check: despite stakeholder pressure, companies continue to succumb to pressures of competitive markets that demand fast and high returns, resulting in more harm to people.

The most welcome development in 2019 occurred in the government radial, with the push primarily in Europe for laws that require companies to take human rights into account in conducting business. The first such law was passed in France in 2017 as the French Duty of Vigilance Law, requiring companies with more than 5,000 employees to create and adhere to a “vigilance plan” to prevent violations of human rights throughout their value chains. The Netherlands adopted a similar law in relation to child labor, and to date six more European legislatures have begun to draft laws. My 2020 class will closely watch this space, while continuing to examine the other forces that we hope will strengthen the web of corporate accountability.