The debate over whether human rights are indeed “universal” or are to be understood and applied differently depending on national, regional, cultural or religious contexts (i.e., “cultural relativism”) is well known. In today’s world, where political leaders in some established democracies appear to be sounding the retreat from liberal internationalism, and where religious extremists are bent on dividing the world into “us” and “them”, this debate is particularly important. The debate is also very emotive and, usually, subjective. Against this background, it is useful to identify more objective, even scientific, means or indicators to assess whether the world is moving away from, or towards, universal human rights. State adherence and commitment to international human rights law is one such indicator.

The core human rights treaties fulfill a central function in the global human rights system. By voluntarily acceding to them, states bind themselves into a comprehensive framework of human rights obligations. In so doing, states express, in a binding legal manner, their commitment to these norms, and their determination to gradually bring their national laws and practices into line. Levels of treaty ratification, over time and across the full UN membership, therefore provide a powerful indicator of “the march of universality”.

Flickr/Alex Proimos/(Some Rights Reserved).

Moroccan peaceful protest against discrimination.

Notwithstanding, when acceding to international human rights treaties, some states enter “reservations” that limit, either generally or partially, the scope of application of the treaty in domestic law. These may take the form of so-called “general reservations” under which a state only accepts obligations under a treaty insofar as those obligations are compatible with the tenets of a given religion. For example, Saudi Arabia maintains a general reservation to the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), which reads:

In the case of contradiction between any term of the Convention and the norms of Islamic law, the Kingdom is not under obligation to observe the contradictory terms of the Convention.

A reservation may also be “partial” or “specific”, limiting the application of a certain treaty article, while leaving other treaty obligations intact. For instance, a reservation entered by the Principality of Monaco to the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) reads:

The Principality of Monaco does not consider itself bound by Article 16, paragraph 1 (g), regarding the right to choose one’s surname.

Reservations (general or specific) have a significant negative impact on the enjoyment of human rights. If a given treaty or article is the subject of many reservations, it is clearly suggestive of a perceived incompatibility between the rights concerned and the cultural norms or religious sensibilities of certain states. The presence of reservations reinforces the arguments of cultural relativists, while the withdrawal of reservations—or acceding to a convention without reservations in the first place—is a powerful indicator of universality.

The March of Universality?

Between 2014-2016, the Universal Rights Group (URG) led a major international project to track levels of ratification of the core human rights treaties around the world, and to map all reservations to those treaties. Some of the top-line results can be seen in Figure 1 below. The final report of the project can be read here.

Figure 1: The March of Universality

Source: URG “March of Universality” report, 2017.

As can be seen from the graph, the number of ratifications for all treaties has increased exponentially over the past half century. At the same time, there has been a clear decrease in the frequency with which ratifying states enter reservations under those treaties (either general reservations to the whole treaty or specific reservations to certain articles) and a clear increase in the frequency with which states parties are withdrawing or lifting already-entered reservations. This appears to support the argument that states are moving towards a universal understanding of and commitment to human rights.

An important counter-argument, of course, is that states may ratify a treaty or withdraw reservations for purely reputational purposes—with little or no genuine intent to fulfill its human rights obligations on the ground. As Emilie Hafner-Burton pointed out in her research:

“For most countries, there is little or no apparent relationship between a government’s formal commitments under international human rights laws and their actual respect for human rights. In some cases, the trends actually point in the wrong direction—once a country joins a treaty its record of abuse actually gets worse.”

While the willingness of states to pursue the domestic implementation of universal norms has long fallen behind their willingness to discuss, negotiate and commit to new norms at the international level, Hafner-Burton pushes the point too far. It is true that, as she suggests, the worst “human rights abusers” generally have little or no intention of implementing their international human rights obligations. It is also true that the current system works best at protecting human rights where the worst abuses are unlikely to occur. However, URG’s research on compliance counters her claim that there is little or no relationship between formal commitments and actual behavior. On the contrary, for a large majority of states, ratification of a human rights treaty does represent a real political commitment to implement those norms, and the lifting of reservations does reflect a determination to do so more fully. The principal problem is, rather, that the international human rights system is very poor at measuring progress with implementation.

URG’s analysis also found that states have even made progress in lifting “religion-based reservations.”

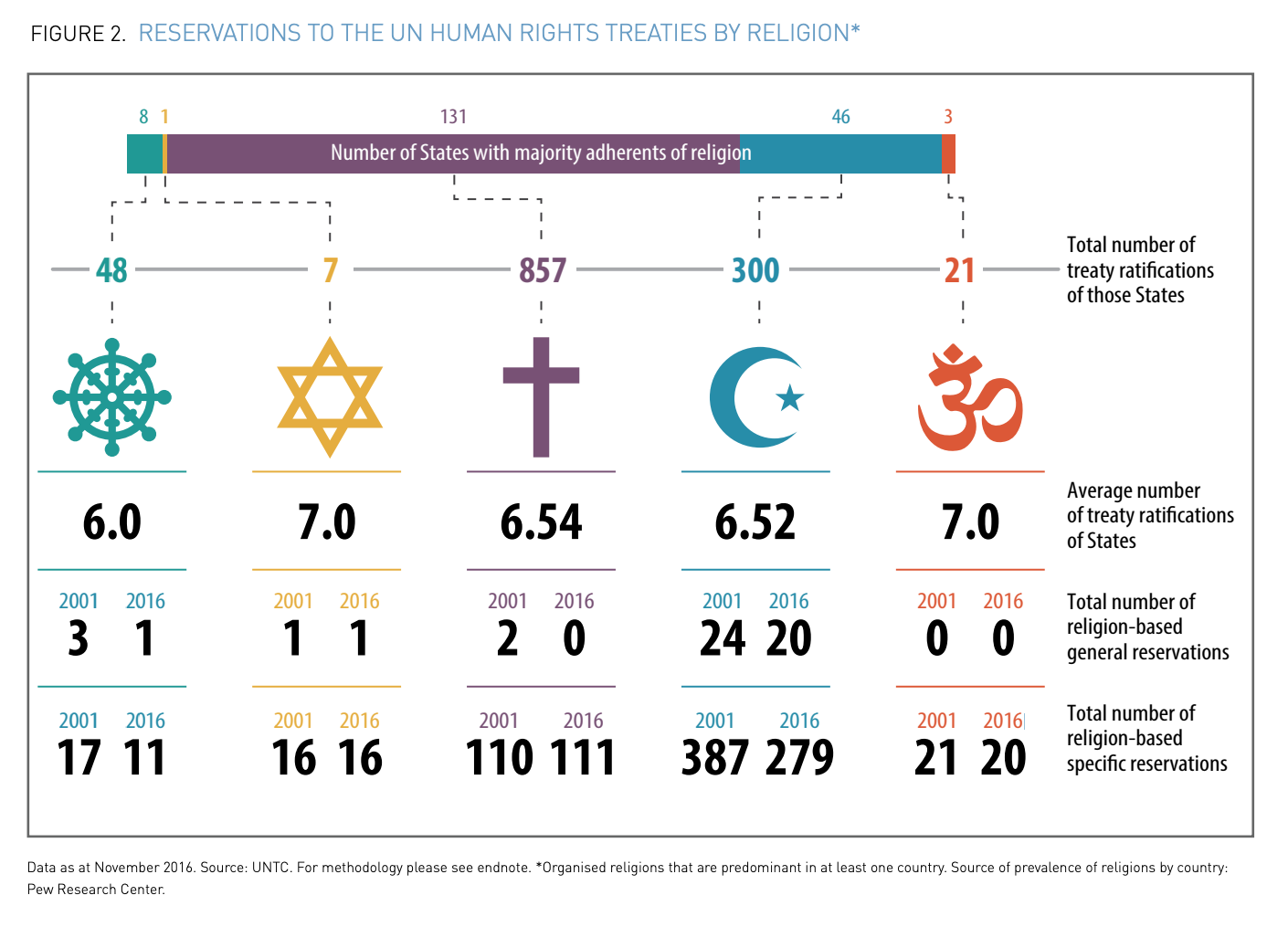

URG’s analysis also found that states have even made progress in lifting “religion-based reservations”: reservations that are, or appear to be, based on an understanding that certain universal norms are incompatible with religious belief or doctrine (see Figure 2). In a trend with important positive implications for the universality of human rights and the determination of states to strengthen their commitments and obligations under international human rights law, between 1991 and 2012, nine states withdrew religion-based general reservations to the core UN human rights treaties (all but two of the lifting States are members of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation), and 19 States lifted religion-based specific reservations (17 OIC States, plus Mauritius and Singapore).

Figure 2: Religion-Based Reservations Source: URG “March of Universality” report, 2017.

Source: URG “March of Universality” report, 2017.

Again, some commentators see this as mere “window-dressing”. However, URG’s analysis of reservations lifted by Indonesia, Morocco and Tunisia show that these decisions were the external manifestation of deeply sensitive domestic political questions about the relationship between universal human rights norms and national/local culture, religious beliefs and traditions. They also reflect the final settlement or outward expression of complex domestic debates between relevant stakeholders (different government ministries, lawyers, religious leaders, NGOs) about how best to guarantee the “promotion and protection all human rights and fundamental freedoms”, while bearing in mind “the significance of national and regional particularities and various historical, cultural and religious backgrounds” (as quoted in the Vienna Declaration and Program of Action).

In short, these case studies show that many states are working actively (though, too often, invisibly) to broaden the boundaries of universality, even across sensitive issues that touch on matters of religious belief or doctrine. This is, in turn, an important and welcome sign that the international community may be moving towards—not away from—a universalist understanding of and commitment to human rights.