Digitalization in Pakistan and its promise of “cross-sector socio-economic development” are centered around the country’s national identity system. Initially a paper-based form of identification, the National Identity Card was computerized in 2001 by the newly-formed National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA). This federal body transformed the digital ID landscape by incorporating new markers of identity, such as biometrics, within a digital citizen database.

However, the national identity system is failing to cater to the needs of various marginalized communities, and is also a potential threat to citizens’ right to privacy because it is centralized under one authority.

In addition to revealing an individual’s full name, date of birth, and addresses, the Computarized National Identity Card (CNIC) includes a unique 13-digit ID number which is made up of the individual’s domicile, followed by a family number that forms each individual’s family tree, after which an odd or even number is assigned denoting the individual’s sex. The presence of the gender marker within the identity number is particularly sensitive for transgender communities since it will always reveal the gender they were assigned at birth, even though their chosen gender is already marked in a separate category on the card.

Each ID card was associated with the individual’s father, which women were obligated to replace with their husband’s name upon marriage. The consequences of such a patrilineal identification system are especially challenging in cases of divorce or single-parenthood, where the absence of a husband or a father poses barriers for women and children in all bureaucratic processes where their identity must be verified.

This requirement of the father’s name also raises concerns for orphaned children, those adopted by single mothers, or those conceived using a sperm donor. Although NADRA has created policies for registering children in orphanages under the head of the orphanages, it has not yet accounted for those orphaned children who are not in orphanages and are with or without known parentage. In fact, NADRA has revealed that it assigns a random name from within the citizen database as the child’s father in order to issue an ID card because the field cannot be left blank.

These nuances expose the limitations in the design of the digital ID system in place, in that the markers of identity fed into the system are so rigid that they fail to cater to the many ways one might fall outside of the makers of the system might be considered for the ‘average citizen’.

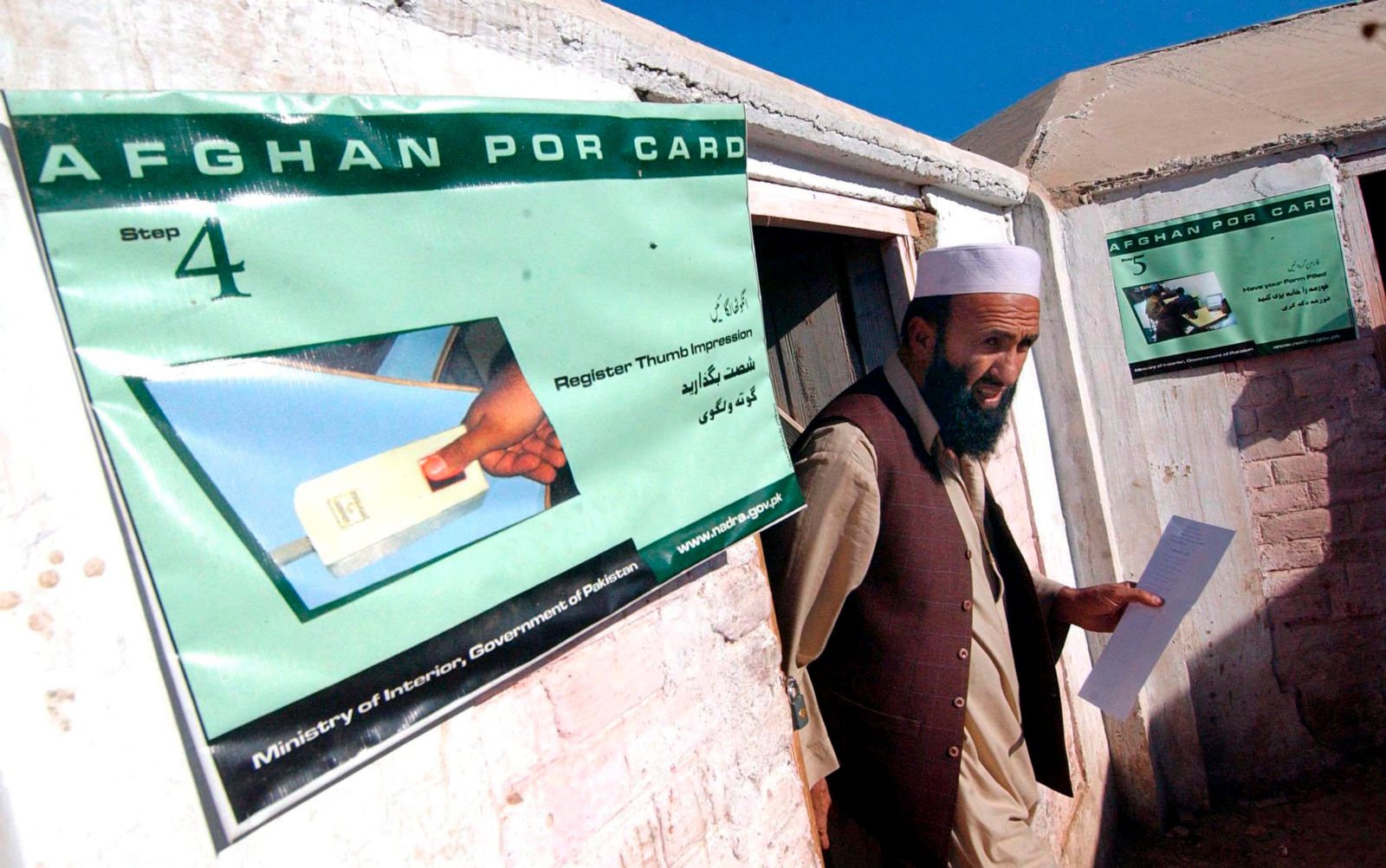

Exclusion from the digital ID system of Pakistan is not just a consequence of a poor design; it is sometimes intentional. Already vulnerable communities are pushed further into the margins when their CNICs are forcefully suspended or blocked, on the suspicion of their being an ‘alien.’ The Afghan refugee community is usually targeted with the suspicion of possessing illegal CNICs, because of which the Pashtun community is also subjected to increased profiling.

The process of re-verification that follows a blocked or suspended family tree is made even more difficult by the requirement of documentation as proof of citizenship. Bihari and Bengali-speaking individuals often face similar issues in being denied the acquisition or renewal of citizenship despite having the documents to show that they have been residing in Pakistan since before 1978, as required by law. This denial of citizenship renders these communities as stateless and bars them from the centralized digital landscape.

The Afghan refugee community is usually targeted with the suspicion of possessing illegal CNICs, because of which the Pashtun community is also subjected to increased profiling.

The CNIC number—as the most widely applicable form of digital identity—is linked to a number of public and private services, including banking, telecommunication, housing, vehicle registration, utility billing, travel, education, employment, and healthcare. This means that exclusion from the system brings an individual’s life to a halt, and has been particularly detrimental in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, since testing and vaccination, along with relief programs are all contingent on the existence of a valid identity card.

A centralized digital ID system is characterized by data sharing within different institutions involved in the system. In Pakistan, NADRA’s citizen database is at the heart of the operations of many other public departments such as the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority, the Federal Investigation Agency, and even the Federal Board of Revenue. Despite its centrality to the digital framework, the citizen database has been subject to data leaks more than once.

Yet NADRA either denied any occurrence or shirked accountability for leaks that do not occur directly from their servers, shifting the onus of responsibility onto the institutions that they have shared citizens’ data with, such as the Punjab Information Technology Board (PITB). This incident not only demonstrates how NADRA’s irresponsible data sharing is linked to the sale of citizens’ data online. It also highlights that NADRA is indifferent to citizens’ right to privacy by absolving itself of all responsibility for data leaks that occur. An absence of any legislation on data protection only further allows NADRA to escape accountability.

By virtue of maintaining a data warehouse that is so critical to the functioning of e-governance initiatives being introduced, NADRA as an institution is central to Pakistan’s digital ID landscape. This gives NADRA a lot of power over matters pertaining to the citizen and the state, which it has been criticized for in its arbitrary deployment of this power in the suspension of citizenship, which the Islamabad High Court (IHC) recently ruled to be unconstitutional

But there still remains very little discussion in the public domain regarding the undemocratic nature of NADRA’s practices. The IHC’s judgement should have opened up a wider discussion questioning NADRA’s authority through dialogue with the communities that are impacted the most by its exclusionary policies. The issues raised by these communities must be addressed immediately by the relevant policy-makers.

The overall problematic nature of the digital ID landscape, however, would require fundamental changes in its design. The centralized system not only makes the citizen database more vulnerable to leaks and breaches, it also restricts access to various public and private services to those citizens who possess an ID card. A more accessible and citizen-friendly digital ID system would perhaps be more decentralized, and involve multiple ID systems within a larger digital framework.