The idea of humanity as subject and nature as an object to be tamed has bred a philosophy of conquest, enabling five hundred years of violence against Indigenous peoples and their ways of life. Ultimately, it has also led to a planetary crisis. From the moment that Europeans arrived on South American soil, the West has assumed that it knows better than the Indigenous peoples native to their land. In the context of a global climate disaster, it is high time the heirs of this legacy learn to listen.

In recent years, some Amazonian Indigenous groups have harnessed cinema as a medium through which to articulate their cosmologies on their own terms. Often experientially focused, these works enable the transmission of Indigenous ways of being in the world, defying the colonial narratives that have for centuries been imposed on them from outside.

This is a groundbreaking development, because film, as a broadly accessible medium, enables a mode of self-representation that has the potential to reach a wider audience than ever before in the Indigenous context. Filmic expressions of Indigenous peoples’ intimate relationship to land, in turn, open the way for a broader recognition of their claims to territorial sovereignty. In this sense, the nature of cinema as an affective form also invites us non-Indigenous viewers to reimagine our relationship with the vitality of our planet as a whole—to see that it lives and breathes, after all.

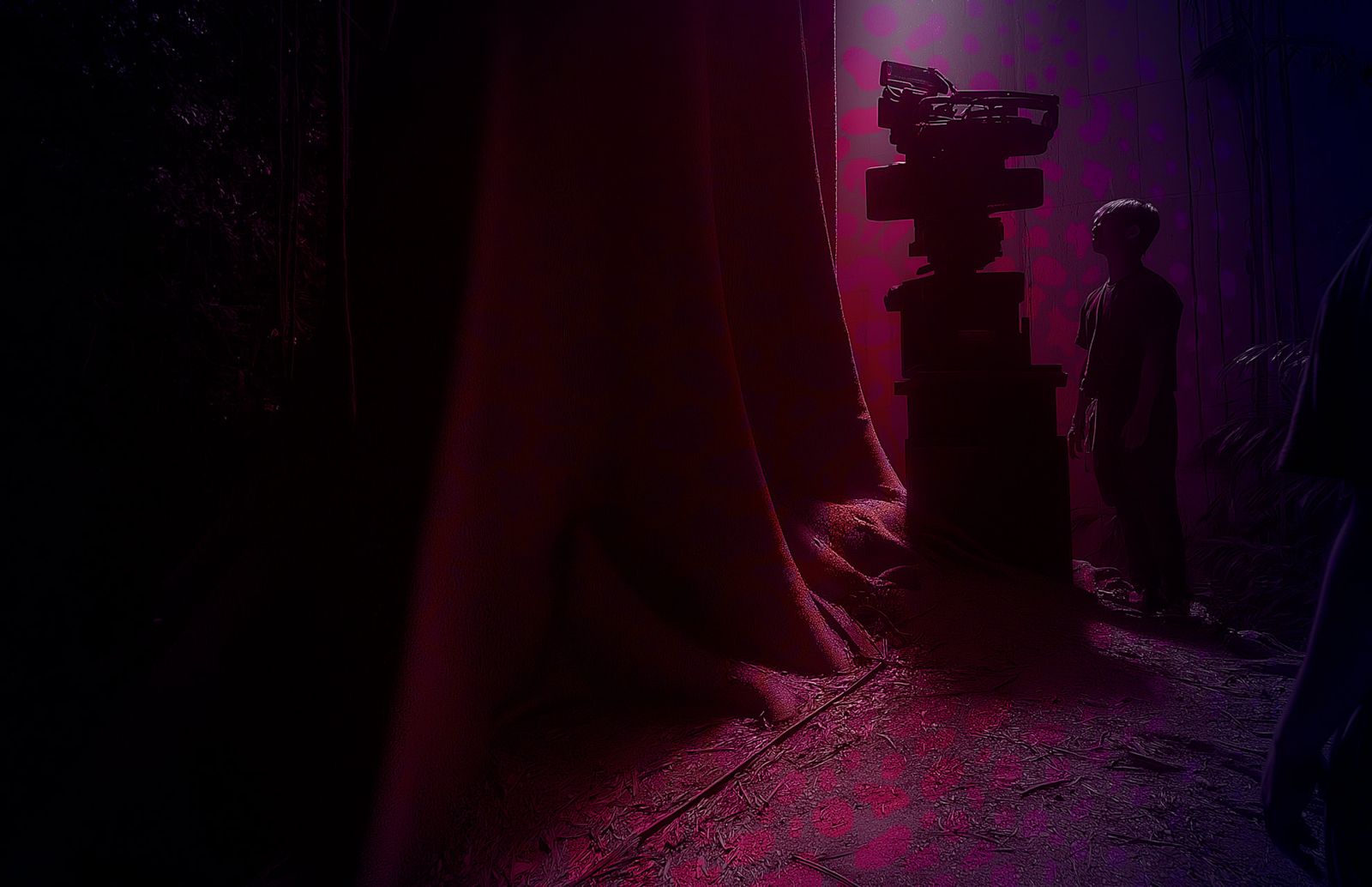

Two recent Amazonian films exemplify such possibilities. Lithipokoroda (2021), by Lilly Baniwa, is an Indigenous performance manifesto from São Gabriel da Cachoeira, Brazil. It follows an ancestral woman walking from the forest to the maloca [longhouse] as white men destroy the land, affirming that Indigenous knowledge endures despite violence. Bakish Rao: Plant Resistance (2024), by Denilson Baniwa and Comando Matico, is a science fiction short that reimagines resistance from the perspective of plants in Peru, critiquing ecological destruction while envisioning interspecies resilience.

Both films decolonize the Western language of film to foreground distinct Indigenous worldviews. Both encourage a reimagining of the viewer’s own relationship with the natural world. To embrace Indigenous cinema, then, is to begin to honor the knowledge and sovereignty of peoples to whom respect is long overdue.

Film as power

Film is a famously powerful language. At its inception at the end of the nineteenth century, narrative-less film brought humanity a vertiginous encounter with modernity. Since then, it has passed through radical avant-garde subversions and been used as a tool of political resistance from Cuba through to Mozambique. More recently, it has been employed as a way to make tangible some of the darkest horrors of our past. It is not so surprising that Indigenous communities are now turning to this affective medium as a form of creative expression.

I believe that cinema can influence our understanding of the world because of its potential to trigger an aesthetic encounter—to move a viewer by provoking an emotional response that transcends linguistic explanation or thought. This feature is powerful for humanity as a whole, not least because alignment with our intuitive experience is a doorway to reconnecting with our natural world. It also reflects how much modern-day academia, founded upon the rationality of Enlightenment thought, has consolidated a world divorced from its embodiment. As Indigenous leader David Kopenawa captures in The Falling Sky, our “inert” writings “do not speak,” and in circulating them, humans “only end up knowing what is already inside their minds.”

More thoroughly embodied forms of knowledge edge us closer to that which Indigenous communities across the globe have known all along—that the Earth “speaks.” If this idea seems convoluted or remote, it is because it can only be truly understood by sensory experience, not thought. This is where the affective nature of cinema has great potential.

Indigenous cinema as resistance

One of the first examples of Indigenous creative agency exercised through Amazonian cinema is seen in two films of the Kayapó in the late 1980s. These films involved collaboration between British television, anthropologists, and Kayapó Indigenous communities, the latter of which consciously harnessed their appearance on camera to record their resistance movement against a hydroelectric dam project in the Altamira area of the Brazilian Amazon. The protests eventually forced the World Bank to withdraw its loan and, ultimately, caused the project to collapse.

While in this instance the Kayapó did not have full authorial control, their active participation sowed the seed of Indigenous creative sovereignty in film as a form of activism. The Amazonian Indigenous filmmakers of today are carrying this torch forward.

Lilly Baniwa’s Lithipokoroda gives a creative voice to Indigenous youth from the most Indigenous city in Brazil. While the images of destruction that follow the protagonist as she moves through the forest are striking, later shots of Indigenous people speaking to the camera, repeating “enough,” and utilizing technology as a vehicle for self-expression, help enunciate their claim to continued self-determination. The creative process enables them to break free from the limitations of the rationalist European worldview that has been imposed upon their people for centuries.

Denilson Baniwa and Comando Matico’s Bakish Rao: Plant Resistance, meanwhile, is even more experimental in its approach. Told via the perspective of plants facing an onslaught of invasive palm oil cultivation, the film decentres the human perspective and communicates the presence of nonhuman interlocutors. As such, it foregrounds the limitations of human languages and defies the anthropocentrism of predominant understandings of ecology.

By embracing the growing production of Indigenous cinema, viewers can better understand the significance of territory to Indigenous communities, thus fostering more informed respect for their right to self-determination. If we are to halt cycles of violence and environmental collapse, we must also reimagine our relationship with the nonhuman life that sustains our planet. Indigenous cinema can be a gateway, encouraging us to pay attention to our being—a being innately intertwined with nature itself. The question, now, is whether we are prepared to listen.