In a recent book, Local Maladies, Global Remedies: Reclaiming the Right to Health in Latin America, I argue that, during the last decades, the transformations of the right to health in the Global South were driven by major epidemiological events and by the economic interests in the pharmaceutical industry (i.e. “Big Pharma”).

The first global epidemiological event that transformed the right to health was triggered by the HIV/AIDS virus in the 1990s and early 21st century. The emergence of health as a right that could be enforced in court was due in large part to the activists and litigants—in many cases people infected with the virus—who boldly filed the first lawsuits demanding antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) from their countries' health systems.

During this period several examples stand out: the iconic case of the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) legal mobilization in South Africa around a drug to prevent mother-to-child transmission of the virus (Nevirapine); the activism in favor of generic ARV drugs led by the government of Fernando Enrique Cardoso and by global activist networks; and the Colombian Constitutional Court cases on access to HIV/AIDS treatment.

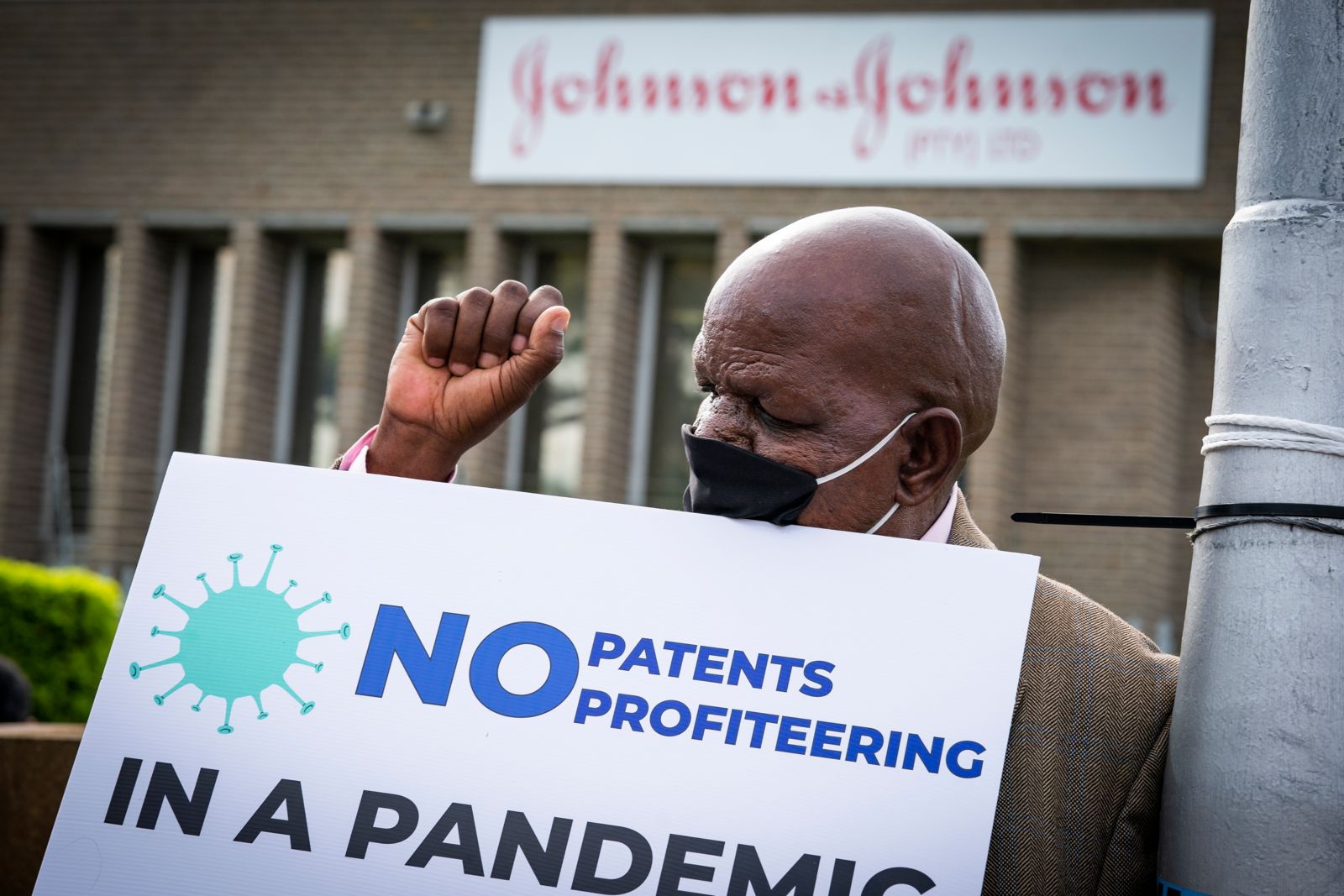

The right to health was transformed during this period into a tool to confront an intellectual property regime that favored the economic interests of Big Pharma at the expense of the well-being and lives of millions of vulnerable people.

The second major event that I analyze in my book is the global epidemiological shift towards chronic and non-communicable diseases such as cancer. In this epidemiological watershed, the right to health has undergone a rapid process of pharmaceuticalization.

The right to health was transformed during this period into a tool to confront an intellectual property regime that favored the economic interests of Big Pharma at the expense of the well-being and lives of millions of vulnerable people.

The pharmaceuticalization of healthcare is evident, for example, in the emphasis by physicians on pharmacological treatments over other types of alternatives (preventive or public health); in patients' preference for brand-name drugs rather than generic alternatives; in the impact that the purchase of brand-name drugs has on public health spending; and in the explosion of litigation in countries such as Brazil and Colombia centered on the demand for high-cost biotechnological drugs.

A perverse effect of pharmaceuticalization is that, in order to realize the essential core of the right to health, governments are increasingly dependent on the availability of drugs whose cost is disproportionate to the financial capacities of the health systems of low- and middle-income countries.

The third major epidemiological event that my book addresses is the current Covid-19 pandemic. What U.S. President Biden called a "global tragedy" is represented not only by the more than six million victims of the coronavirus to date, but by the great global disparities in access to vaccines and basic health services needed to treat the effects of the virus. Evidence of these disparities is that nearly 79% of the available vaccines had been distributed in high-income countries.

While there are good reasons to believe that governments are primarily responsible for such a "global tragedy," and that presidents such as Trump or Bolsonaro could be guilty of crimes against humanity due to their mishandling of the public health crisis unleashed by the pandemic, the global pharmaceutical industry was also instrumental in the lack of vaccine availability in the Global South.

More concretely, Big Pharma's patents on its vaccines led to a scenario of profound inequality between the Global North and the Global South. This was affirmed by the governments of countries such as India and South Africa, who in October 2020 demanded before the WTO a patent waiver on coronavirus vaccines. This request was resisted not only by the pharmaceutical industry, but also by powerful governments such as Germany and France.

But despite the fact that the interests of Big Pharma have played a decisive role in the transformation of the right to health over the last three decades, this actor continues to play a secondary role in the literature. A clear expression of this phenomenon is that the duty to take measures aimed at realizing the right to health falls exclusively on the States.

Although some human rights instruments now point to an emerging regime of corporate duties—the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, for example—corporate responsibility for the right to health is still in its infancy.

In my book, I conclude that the academic literature must incorporate a political economy perspective attentive to the role of Big Pharma as a determinant actor in litigation, regulation, and social mobilization around the right to health. Likewise, human rights instruments must transition to a polycentric conception of duties that is not only centered on the state, but on non-state actors, such as Big Pharma.

One of the most important lessons learned from the HIV/AIDS pandemic is that the fulfillment of the right to health is too important to be left to governments alone.