Broad global movements to advance human rights occasionally intertwine with feminist movements, each influencing the other to varying degrees over time. And feminism, ever ripe with controversies both internal and external, has recently seen a resurgence of second-wave thinking that foregrounds women’s victimhood. Reductive portraits paint women as the victims of interpersonal violence, leading to debates in feminist and human rights circles about who is entitled to our collective concern, even policing the use of terms like “gender” and “sex,” as this essay explores.

While the #MeToo movement has been exciting, massive, surprising, and potentially revolutionary, some of the movement’s simplistic messages are less than helpful. For instance, “Believe Women” is meant to serve as a needed corrective to the decades of doubt female victims of sexual harassment and violence have routinely faced. Yet it also seems to imply that women are one-dimensional truth vessels, not complex, imperfect human beings. “Believe Women” does little to assuage the concerns that many people (including feminist lawyers and scholars) have raised about inadequate due process in the wake of sexual misconduct charges on college campuses and elsewhere. It’s unclear how “Believe Women” applies to female abusers and enablers (such as those who facilitated the abuses of Jeffrey Epstein and Harvey Weinstein) or to male victims, such as the thousands of children around the world (predominantly boys) who were once routinely disbelieved when reporting abuse by Catholic clergy.

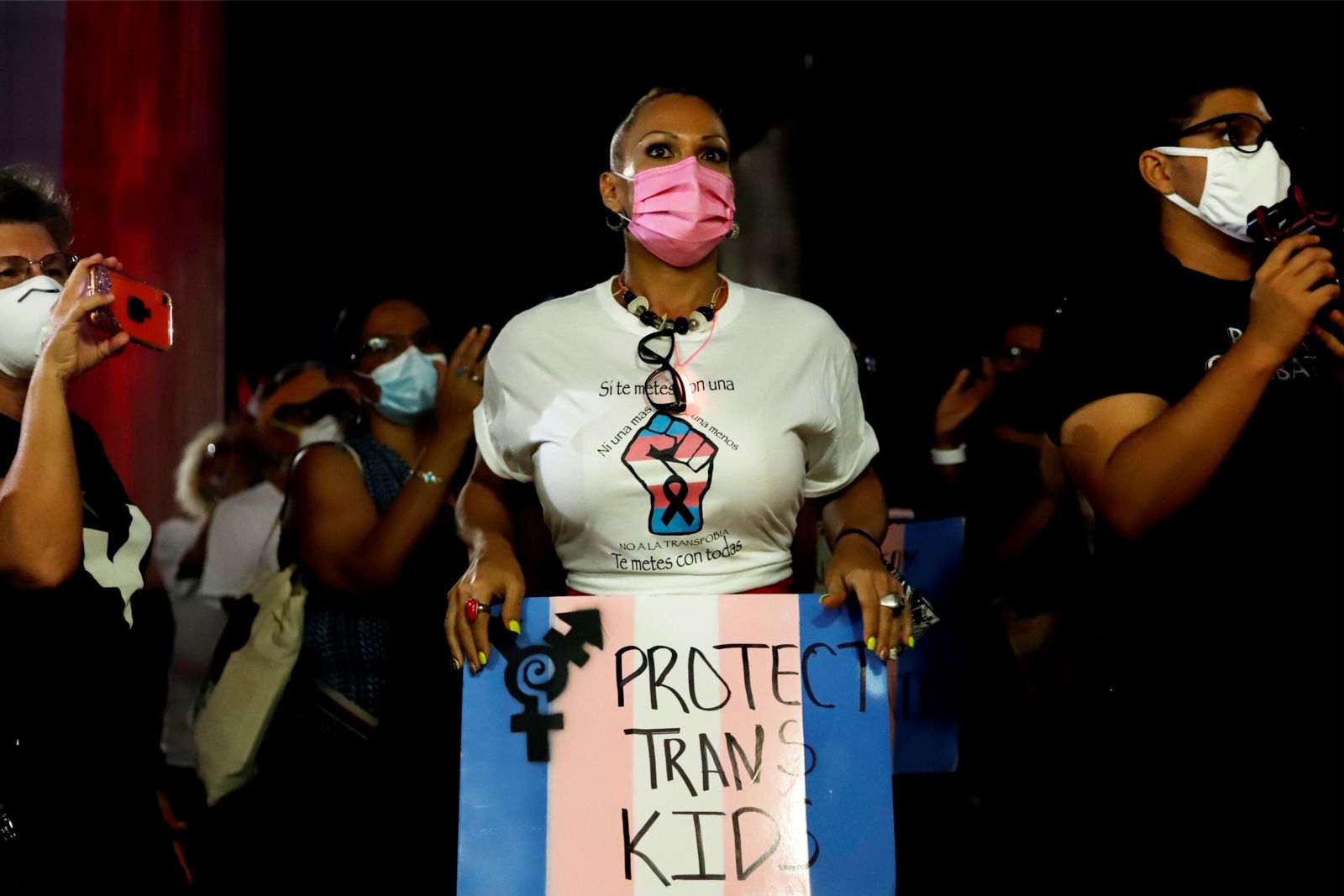

One might be unsurprised to find simplistic slogans like “Believe Women” in mass public discourse, but the resurgence of essentializing, purportedly feminist thinking can be seen in other contexts, including human rights-based advocacy and international policymaking. Work on human trafficking, sex work, armed conflict, and gender-based violence often reflect uncritical “rescue” tendencies, and contemporary organizers who identify as feminist are advancing seemingly outdated ideas about women and gender. So-called feminist activists in Europe, the US, Australia, South Korea, Mexico, Brazil, and elsewhere are advancing a decidedly anti-trans agenda. Some groups decry the replacement of the category “sex”, which they view as fixed, with the category “gender identity”, which allows for a fluidity they find offensive.

In the retro “Declaration on Women’s Sex-Based Rights” the signatories want feminist advocacy to apply to cis-gendered women alone, claiming that inclusive gender categories discriminate against women. They have turned this belief into a call to discriminate against others in Article 4: “States should uphold the right of everyone to describe others on the basis of their sex rather than their ‘gender identity’, in all contexts” (emphasis added). Here, a human rights-style call to action runs directly counter to fundamental notions of equality that undergird the human rights movement.

The non-intersectional “women only” thread can also be found in other, more influential emerging movements. An instructive example is COFEM, the Coalition of Feminists for Social Change, founded in 2017 and describing itself as “an advocacy collective” working globally on violence against women. COFEM also resists expanded definitions of gender, and it’s gaining some real traction among actors working in humanitarian and human rights spaces.

COFEM’s publications put forward a perspective, which, most prominently, challenges inclusive definitions of gender-based violence (GBV). COFEM presents the belief that GBV only applies to women and girls as axiomatic; it asserts that the word “gender” itself should focus on the inequalities experienced by women and girls. They complain that, “GBV is being (re)interpreted regularly to emphasize gender roles and identities as they affect all people, with these definitions often specifically calling attention to violence against males and violence against LGBTQ and other groups broadly” (emphasis in original, page 3). They call out the EU and USAID in particular.

The relentless drumbeat of women as victims thwarts feminisms’ more emancipatory goals.

COFEM claims the feminist mantle for themselves (excluding those of us who have persistently articulated feminist arguments for more inclusive understandings of gender), maintaining that “expanded definitions of GBV fail largely to reflect feminist theory and principles.” This overlooks decades of work that, for example, offers a feminist take on masculinized dominance and feminized submission in cases of male-on-male sexual violence. Look no further than prison contexts in which sexually dominant prisoners call the men they rape, “my woman” or “my bitch.” Victimized inmates, who are sometime virtually “owned” for years, can be expected to do laundry, adopt feminized ways of behaving, and remain submissive to “their man.” Yet, by COFEM’s logic, a gender lens has no place here.

COFEM’s framing also overlooks feminist and intersectional critiques of essentializing portrayals of women as victims. Ratna Kapur and others have argued for decades that reductive victimization rhetoric in some forms of human rights advocacy is far from emancipatory for women; indeed it reinforces racialized tropes about “Third World” women in need of outside rescue. The relentless drumbeat of women as victims thwarts feminisms’ more emancipatory goals.

Consider this assortment of well-documented phenomena: hegemonic masculinity norms drive homophobic violence throughout the world. Intersex infants undergo cosmetic genital surgeries to conform their appearance to a particular sex before they can consent. Transfolk, native women, and disabled persons are at enormous risk of campus sexual victimization in the US despite the public emphasis on white, straight, able-bodied women. Afghani men who practice bacha bazi sexually exploit boys who are forced to dress and dance in a feminine manner. The idea that gender-based violence is a concept applicable to only one group thwarts more complicated intersectional analyses and denies reality. Yet this argument is gaining steam in international circles.

When we expand rights, particularly for people who do not conform to traditional, patriarchal notions of who women and men should love, or how people should identify and present themselves, this is a clear win for feminist principles.

At the same time, as resistance to progress on LBGT+ rights hardens in many parts of the world, women’s rights NGOs are increasingly likely to see strong alliances with LGBT+ groups as a risk, rather than as an opportunity to advance shared interests. This division is especially counterproductive as paranoid politicians in Latin America and elsewhere crusade against so-called “gender ideology,” simultaneously aiming to strip women and LGBT+ persons of fundamental rights.

I’ve spent decades working in movements calling for resources and attention to a range of sexually victimized people, some of whom are men and boys. I’ve worked with academics and advocates in contexts as diverse as prisons and jails, armed conflict and humanitarian settings, schools, immigration detention, and religious institutions. The near-total absence of donor funding for male victims in these contexts is a constant point of advocacy, of course. Yet never have I heard those working in these spaces call for funds to be transferred away from women and girls and moved to programs for men and boys. Nor for LGBT+ programs. Nevertheless, the oft-repeated funding threat triggers alarms among underfunded women’s organizations, thereby generating buy-in for exclusionary strategies that claim “gender” for straight cis-women.

Meanwhile the EU Court of Justice and high courts in Belize, Colombia, New Zealand, Thailand, the US, and elsewhere have ruled that prohibitions on sex discrimination ought to also prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and/or gender expression. When we expand rights, particularly for people who do not conform to traditional, patriarchal notions of who women and men should love, or how people should identify and present themselves, this is a clear win for feminist principles. In contrast, reductive “women-only” discourses try to lock down the meaning of gender, just as they lock out other claimants seeking justice. This must be roundly rejected by those of us who value inclusive ways of advancing human rights.

This piece is part of a series published in partnership with Occidental College’s Young Initiative on the Global Political Economy, division of Social Sciences at Arizona State University, and USC’s Institute on Inequalities in Global Health. It flows out of a September 2019 workshop held at Occidental on “Cross-cutting Global Conversations on Human Rights: Interdisciplinarity, Intersectionality, and Indivisibility.