Support for Black Lives Matter (BLM) soared to new heights after George Floyd’s killing this past summer. It has since slipped, however. According to a September 2020 poll, only 52 % of the U.S. public had a favorable view of BLM a few months ago, down from a high of 61 % three months earlier.

Black Lives Matter was an important factor in the recent U.S. presidential elections; 90 % of respondents in one large poll reported that the anti-police protests were “a factor” in their voting, while roughly 75% said it was a “major factor.” Views about the significance of these protests vary by political partisanship, however. Democrats were energized by them to vote for Biden, while Republicans experienced the opposite.

Religious affiliation also matters, as some of the staunchest anti-BLM people in the U.S. are white evangelicals. Although 56% of respondents told pollsters in late June 2020 that police killings of black men “are part of a broader pattern of how police treat Black Americans,” 72% of white evangelicals said police killings were “isolated incidents.” The U.S. public as a whole has become more critical of police racism and violence, but white evangelicals have remained consistently opposed to such claims.

The issue is much broader than race relations or policing, however. Across a broad range of policies, white evangelicals stand out as one of the most anti-human rights groups in the country. A slew of reports, for example, routinely suggest that white, born-again U.S. Americans are more skeptical than evangelicals of color and non-evangelicals toward admitting refugees fleeing persecution; integrating undocumented individuals into U.S. society; prosecuting police officers suspected of using excessive force; and prohibiting the torture of suspected terrorists.

White evangelical opposition to internationally recognized rights is neither intuitive nor theologically determined. As Peter Wehner, a prominent evangelical Christian and veteran of several Republican administrations has written, the evangelical creed is built on emulating the values of Jesus, whose “energies and affections were primarily aimed toward social outcasts, the downtrodden and ‘unclean,’ strangers and aliens, prostitutes and the powerless.”

Why, then, would white evangelicals differ so markedly from evangelicals of color, given their shared inclusive theology and dedication to applying those theological commitments to politics? Indeed, why would white evangelicals be uniquely indifferent to the plight of all manner of vulnerable groups?

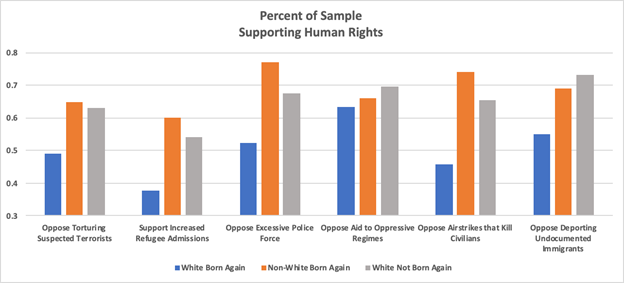

To understand the distinctiveness of white evangelicals on human rights, we asked the survey firm YouGov to poll a nationally representative sample of 2,000 U.S. Americans in the fall of 2018. Of that number, 389 (19 % of the total) reported being both white and “born-again,” a figure comparable to the 17 % cited in other studies. A further 189 respondents (9.5% of the total 2,000) identified as non-white evangelicals, while 1,086 (54 %) identified as white non-evangelicals. The remainder (17.5 %) were either secular or of other faiths.

As the graph below shows, white evangelicals are substantially less supportive of human rights than either evangelicals of color, or white non-evangelicals. (We omit non-white, non-evangelicals for simplicity’s sake; however, their scores are just as rights-supporting as white non-evangelicals and evangelicals of color). Across the board, both non-white evangelicals (represented by the orange bars) and white non-evangelicals (represented by the grey bars) were substantially more supportive of human rights policies than white evangelicals (the blue bars). The smallest but still significant difference was on attitudes toward aid to oppressive regimes.

How should we interpret these differences? Given that both white and non-white evangelicals draw on many of the same written materials, it is not likely that the difference between them lies in opposing theological texts and assumptions. Indeed, a deeper look at the data suggests that it is not evangelical theology itself that is at issue: when we controlled statistically for partisan affiliation (being a Democrat or a Republican) and/or for racial attitudes (a key cause of political party preference), the differences between white evangelicals, on the one hand, and non-white evangelicals and white non-evangelicals, on the other, all but evaporated. According to the same Associated Press post-election poll cited above, roughly 80 % of white evangelicals in the U.S. voted for Trump before or on November 3, 2020.

The origin of these views lies in an ideological struggle within the Republican party in the 1970s, and in white evangelical identification with that party ever since. In the 1980 presidential election, Ronald Reagan ran on a strong “family values” platform, among other things (e.g., small government and a tough approach towards the Soviet Union), and white evangelicals voted for him in droves. Once they solidified their pact with Reagan, white evangelicals absorbed a wider range of messages and political positions advanced by Republican Party elites, including an increasingly anti-human rights stance.

This inversion of democratic theory—choosing policy preferences on the basis of party affiliation rather than the reverse—partly explains how evangelicals turned against human rights.

This finding reflects a central dynamic of public opinion in the United States: As partisanship became acutely polarized in the last 20 years, Americans increasingly sought to reconcile inconsistencies between their party affiliation and their policy views by adjusting the latter to fit the former. Republican voters stick with that party, while Democratic voters do the same with theirs. Thus when party platforms changed, so did the views of voters. Liberal Republicans became conservative Republicans as the party moved to the right, and conservative Democrats became liberal Democrats as that party moved to the left.

This inversion of democratic theory—choosing policy preferences on the basis of party affiliation rather than the reverse—partly explains how evangelicals turned against human rights. The desire to be loyal to the partisan tribe turned evangelicals against a variety of rights-related policies (as, over time, Republicans became less supportive of such rights than Democrats), even as this entailed supporting positions that cut against the grain of Christian teaching.

As political scientists Paul Goren and Christopher Chapp have found, stances on cultural issues lead voters to “sort” themselves into the two respective parties. Once such sorting occurs, voters willingly align their policy preferences on other issues—such as the human rights policies we studied—with whatever their chosen party stands for. It is not evangelicalism itself, therefore, that is the main driver of anti-rights positions. Rather, it is the alliance between white evangelicals and the Republican party—fused by Ronald Reagan in the 1980s—that was key, along with the strong tendency for Americans to take cues from party elites on a wide range of issues. If white evangelicals were to ever allow daylight to creep in between themselves and the Republican party, their views could move in a more pro-human rights direction.

Theologically speaking, evangelical Christianity contains plenty of resources for a more rights-respecting culture. As theologians Luke Bretherton and Nimi Wariboko have each recently shown, Christian scriptures and worldviews can undergird strong evangelical support for political rights and a vigorous “politics of the common life,” in which democracy, concern for the wellbeing of “the stranger,” and social justice are central tenets of their faith. For now, however, it appears that political loyalty based on cultural resonance trumps evangelical theology.