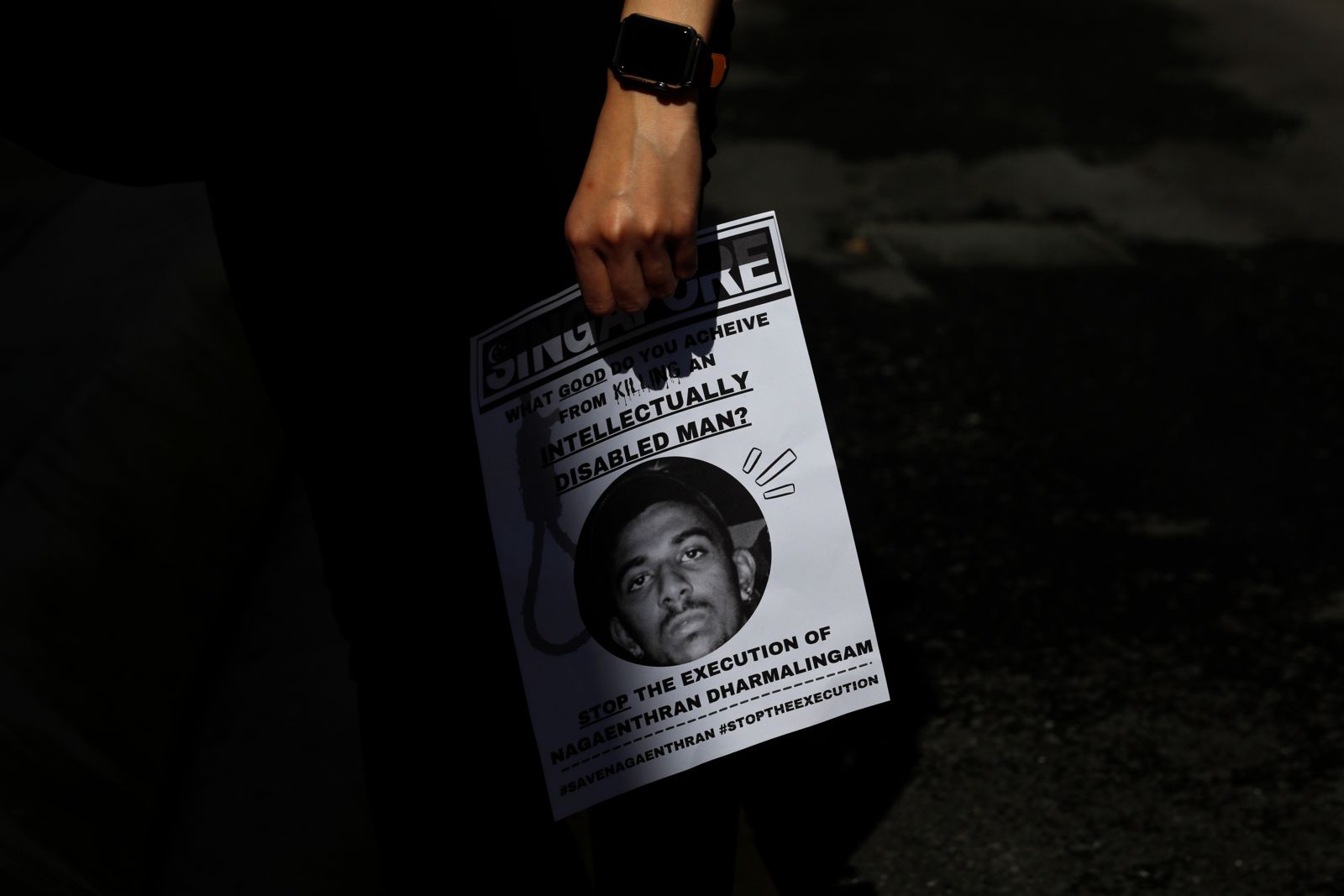

Nagaenthran K. Dharmalingam has spent more than a decade on death row in Singapore, after being sentenced to death in 2011 for a drug offence. Nagaenthran, a Malaysian national, suffers from mental health challenges and has cognitive disabilities – which should provide a legal and moral basis for stopping his execution, as human right groups have rightly pointed out. His execution has been set for April 27. His case has sparked national and international outcry and condemnation from disability rights activists, the Malaysian Prime Minister and King, UN human rights experts, and Virgin Group founder Richard Branson.

Last month, Singapore carried out its first execution since 2019, when Abdul Kahar bin Othman, a local man sentenced to death for drug offences was executed. Nagaenthran is one of four people to have received a notice of execution in Singapore in the past five months. All four cases display eerie similarities: all four were convicted for drug trafficking, and first sentenced to death as a mandatory punishment; all experience serious mental health challenges; two are foreign nationals, and the other two are members of an ethnic minority group. None of them was a major figure in the drug market. These cases are not exceptional. Many, if not most, of the people currently on death row for drug offenses come from marginalized groups.

A report by Harm Reduction International (HRI) found that at least 131 people were executed for drug offenses in 2021 (an increase of more than 300% from 2020), and at least 237 people were sentenced to death for drug offenses in 16 countries. On a global scale, at least 3,000 people are believed to be on death row for drug offenses, if not many more. The report also found that the death penalty for drugs is disproportionately used against people from marginalized communities often experiencing intersecting vulnerabilities, including foreign nationals, women, and people with cognitive disabilities.

Among those confirmed to have been sentenced to death for a drug offence in 2021, around a tenth are foreign nationals. As previously highlighted by HRI, foreign nationals (including migrant workers) are at heightened risk of being tricked or coerced into engaging in the drug market, experience discrimination, and face unique vulnerabilities in unfamiliar criminal legal systems.

The report also found that the death penalty for drugs is disproportionately used against people from marginalized communities often experiencing intersecting vulnerabilities, including foreign nationals, women, and people with cognitive disabilities.

People from ethnic minority backgrounds are also disproportionately impacted by the imposition of capital punishment for drug offenses. In Iran, civil society organizations and the United Nations have denounced a trend of executions against Baloch minority prisoners, many of whom were convicted on drug charges after flawed legal proceedings. Similarly in Singapore, a High Court application filed in 2021 interrogated the overrepresentation of Singaporeans of Malay ethnicity among those on death row for drug offences.

Women also experience unique vulnerabilities both in society and in criminal justice systems and are disproportionately impacted by punitive drug control worldwide. A majority of women on death row in countries that still impose the death penalty for drug offenses, such as Thailand (86%) and Malaysia (95% in 2019), are awaiting execution for drug crimes. Similarly, newly released figures indicate that the majority of women confirmed to have been executed in Iran between 2010 and October 2021 had been convicted of drug offenses.

Finally, an in-depth look at the circumstances of those awaiting execution in Singapore has shed new light on the prevalence of mental health issues, including cognitive disabilities, among people on death row for drug offenses worldwide.

Years of evidence have shown that the death penalty primarily targets the most vulnerable and marginalized people in society. Research shows that the same is true for punitive drug control policies and the death penalty for drug offenses, which are now proven to disproportionately target people living in poverty, racial and ethnic minorities, Indigenous peoples, and other marginalized groups.

The death penalty does not deter drug use or drug trafficking, which means that in addition to being inhumane and unjust, it is also an ineffective form of punishment. It fails to address the root causes of why people use, sell, transport, or traffic drugs. All it does is make vulnerable people even more vulnerable. It stretches an already overwhelmed criminal legal system and increases the number of people languishing on death row worldwide. Governments that retain the death penalty for drug offenses jealously reclaim their sovereignty and point to the many safeguards which are in place (at least on paper) in capital drug cases to justify retaining this form of punishment. But, as recently noted by an activist in Singapore, when a legal system repeatedly and disproportionately affects the most marginalized and vulnerable in society, can it really be described as ‘justice’?