Due to COVID-19 restrictions and emergency measures, the state can more easily justify the arbitrary arrests of protesters and human rights defenders (HRDs), thus elevating the risk of criminalization. It is also much easier for governments to monitor and track their movements both on- and off-line, increasing their vulnerability.

With the virus raging on, the consequences of arbitrary detention and criminalization could be life threatening, which is why preventing unwarranted targeting of dissenting voices and advocating for the release of imprisoned HRDs has never been more critical.

A rise in digital tools and a rise in digital threats

For those who have internet access, bringing discussions about human rights violations online has opened communications channels that have been previously closed. Some HRDs can more easily connect to a Human Rights Council meeting or speak at an African Union event without the financial burdens of long-distance travel. However, many HRDs, communities, and organizations are reporting that they are now further exposed to online harassment, doxing, hacking and censorship. “We have noticed that more and more HRDs are asking questions about digital security and show a good level of awareness of digital threats due to increased exposure to them,” noted one of our colleagues from Protection International Mesoamerica.

One of Protection International’s partner organizations in Brazil was recently attacked with violent and racist comments during a Facebook and YouTube Live session. Vicious, personal online attacks are especially prevalent means of demoralizing minority, women, and LGBTI HRDs, as evidenced by the case of Rosa Luz, who was forced to flee São Paolo after receiving several death threats.

Since the pandemic began, Protection International staff have experienced numerous digital security incidents, including internet throttling in Kenya, at least four instances of online harassment from uninvited virtual meeting attendees, and heightened instances of phishing attempts across multiple institutional email addresses. “The pandemic brought a tremendous increase in phishing attacks, as well as an increase in attacks on tools and services that suddenly everybody needed to use, such as Zoom,” noted Claus Goettfert, Protection International’s IT administrator. “Not only are some defenders explicitly targeted, but these high-impact data breaches and security incidents impact us and our partner organizations as collateral damage.”

Privacy continues to be a luxury, available for only those HRDs who can afford it.

Protection International’s partner organizations have experienced at least 20 digital security incidents since the start of the pandemic, seven of which affected our team’s work in Indonesia. “Digital security is a serious threat. Every month, one of our partner organization’s websites is hacked, which is now happening more often,” noted colleagues from PI Indonesia. In Yogyakarta, a student organization from the Gajah Mada University was forced to cancel an online debate after receiving death threats and being accused of treason. In another case, Ravio Patra, a Indonesian researcher and outspoken government critic, was arrested under the false accusation of inciting riots through WhatsApp.

To proactively counter digital security incidents, Protection International created a Digitalization Task Force specifically to monitor digital incidents, as well as train staff to use and advocate for privacy-friendly platforms, including secure communications tools. To date, approximately 80% of Protection International’s partners have switched to more secure communications channels since the start of the pandemic, but financial restraints are still impeding many HRDs from being able to do so. For example, WhatsApp may be freely included in certain phone plans, while Signal, the more secure messaging app option, is not. Privacy continues to be a luxury, available for only those HRDs who can afford it.

For those HRDs that do not have access to the internet, however, state responses to their protection needs remain even more unsatisfactory and imbalanced. For those rural HRDs that Protection International had been in contact with prior to the outbreak, teams began communicating via radio and podcasts.

In Guatemala, PI Mesoamerica broadcasted a series of messages in Spanish and the Mayan languages of Mam, Q'eqchi and Q’anjob’al spreading information about the psychosocial and gendered struggles that HRDs are currently facing during the pandemic, as well as the importance of preventive protection. The intent is to reduce the feeling of isolation, both physical and perceived, and carry much needed information to hard-to-reach places. It is crucial that governments focus their protection efforts on those that are most marginalized and isolated by COVID-19 restrictions, especially those who are physically and digitally disconnected.

Description: Training sessions on peacebuilding and the Do No Harm principle in the DR Congo. Ephrem Chiruza/Courtesy of author

Political prisoners are exposed to a new form of torture

Governments are also responsible for the protection of those within their care. The distress of being imprisoned during a deadly pandemic is not only cruel punishment, but it is a new and unusual way to incite fear and self-censorship. Heightened risk of COVID-19 spreading in confined, crowded spaces prompted many governments to launch temporary release programs. Many of those, however, excluded most inmates who had been incarcerated for their activism, according to Front Line Defenders. Rather than using the pandemic as an opportunity to finally provide redress for the unjust deprivation of liberty of political dissidents and journalists, many governments continued to use HRDs as threatening examples of what can happen to those that speak out against regimes who refuse to release their stranglehold.

Mr Germain Rukuki, for example, is a Burundian HRD who has spent nearly four years in prison for his activism. He is the founder of the community-based association Njabutsa Tujane, that fights poverty, famine, and improves access to healthcare. Mr Rukuki was arrested by the National Intelligence Service on 13 July 2017 on charges of “rebellion,” “breaching State security,” and an "attack on the Head of State." Germain was interrogated and kept for 14 days without access to a lawyer or his family. After many months of waiting, Mr Rukuki was sentenced to 32-years in prison, although no conclusive evidence was ever presented. Thirty-two years is one of the harshest sentences that any activist has received in Burundi’s history. Thankfully, he was recently released from prison.

The situation for political prisoners in Burundi is dire, especially considering the fact that the Burundian government has been slow to impose measures to halt the spread of COVID-19. Being locked-up in small, cramped cells during the pandemic has undoubtedly caused severe psychological and emotional anguish for arbitrarily detained HRDs and their families. In Mr. Rukuki’s case, reports emerged of an ‘unidentified virus’ sweeping through his place of detainment, Ngozi prison, in June 2020. The situation is all the more worrisome considering the chronic conditions of overcrowding and poor sanitation in Burundi’s prisons. Over the past year, Protection International has supported other organizations’ campaigns for the release of imprisoned HRDs during COVID—including the FIDH’s #ForFreedom campaign and Amnesty International’s Write for Rights campaign—as well as amplifying our own #StayWithDefenders campaign to call attention to Mr Rukuki’s case, but the Burundian government hasn’t shown any willingness to provide respite. The Burundian Appeals Court of Ntahangwa continued to delay the announcement of his verdict as to whether or not his prison sentence will be modified, once again violating his right to a fair trial. After waiting for 62 days past the deadline, it was announced that his sentence would be decreased from 32 years to one. Mr Rukuki is now free and able to return to his family.

“The verdict sets an important precedent for invalidating the criminalisation of human rights defenders,” states Susan Muriungi, Protection International’s Regional Director for Africa. “Germain’s release sends a powerful reminder to all defenders in Burundi and across the African continent. Your work has legitimacy. Your work has value. And you have the right to defend human rights.”

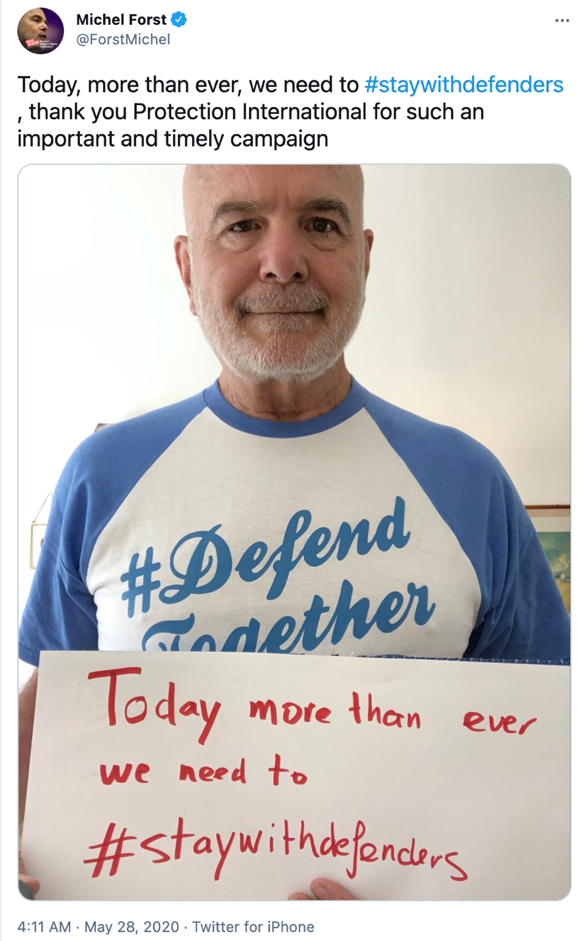

Former UN Special Rapporteur Michel Forst expresses his solidarity with human rights defenders during times of COVID by participating in PI’s #StayWithDefenders campaign

Not only should we continue to better coordinate and advocate for those imprisoned HRDs whose rights have been most restricted, as was done in the case of Mr Rukuki, but we need to focus on preventative protection to better ensure that HRDs’ conditions are less likely to become so dire--this includes counter-surveillance work and network building both on- and off-line. States need to invest in improved policies and mechanisms for HRDs that address protection in a comprehensive, gender sensitive, and intersectional way, allowing for the right to protest both in the digital and physical space without fear of an embellished ‘emergency protocol’ related charge. States should be investing in the citizens who are working towards building back a better version of their country, rather than surveilling, detaining, and putting them behind bars.

This article is part II of a three-part series on COVID-19 and human rights defenders. For more context, here's part I and part III.