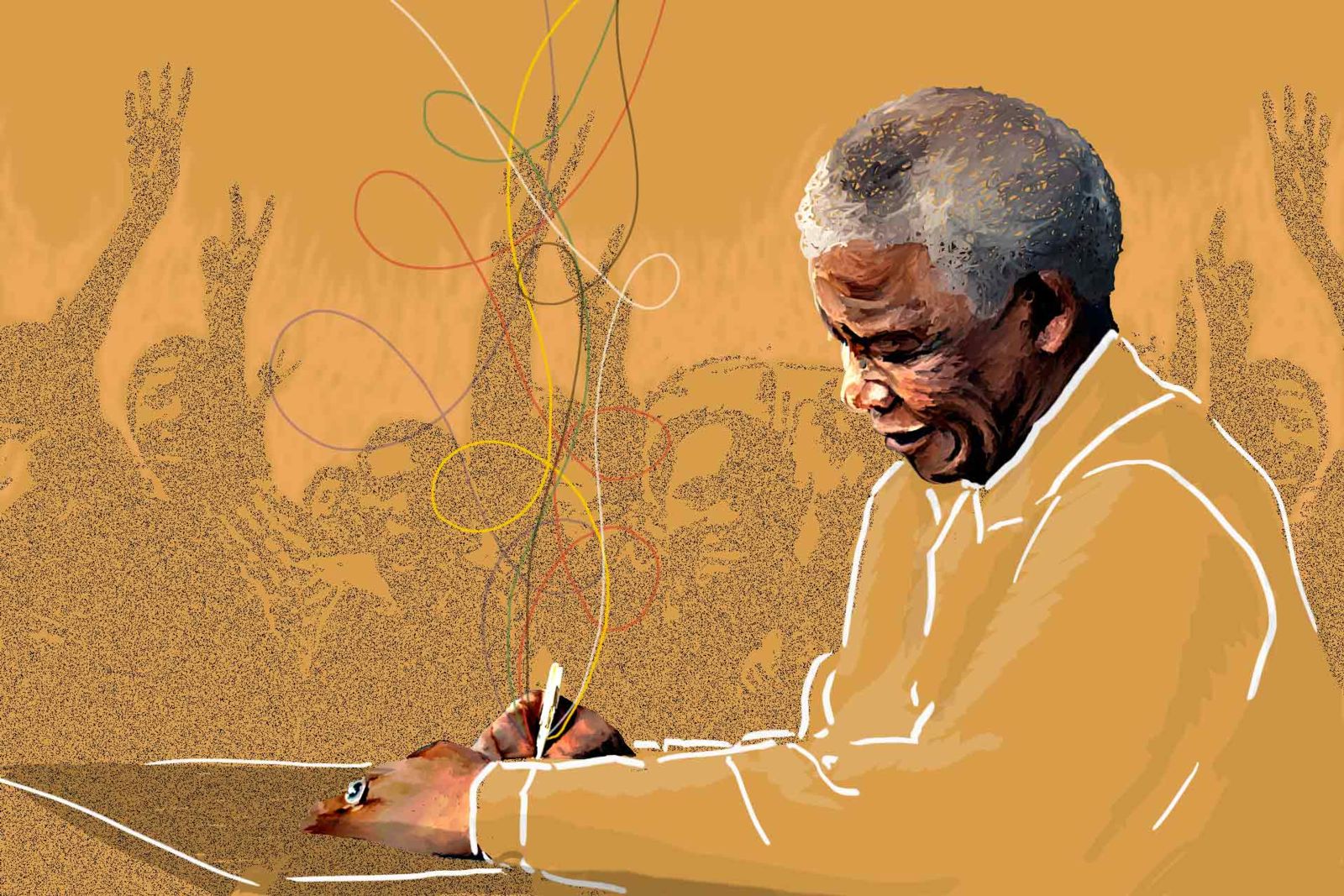

The South African Constitution is one of the most celebrated constitutions in the world because it was drafted by elected parliamentarians and the people through one of the most ambitious public consultation programs in history. The Constitution came after decades and decades of a globally supported struggle which led to the release of one of the most famous political prisoners in the world, Nelson Mandela, who was instrumental in peacefully wrestling power from the apartheid government and averting the large scale civil war that the world had expected.

In continuing the tradition of public engagement that defined the constitution-making process, The Constitution Hill Trust (CHT) founded in 2006 to champion constitutionalism in South Africa, developed a virtual exhibition on the making of the South African Constitution entitled Our Struggle, Our Freedom, Our Constitution which was launched on 24 September 2020. There was an urgency in making this history available because we cannot make sense of present-day South Africa and its challenges without understanding the foundation upon which our constitutional democracy is built.

There were three challenges we had to consider in creating this project. The first is the increasing fragility of democracies across the globe. The second challenge is the growing accusations either that our Constitution is a ‘sell-out’ document, or that it has not delivered on its transformative potential. These contextual challenges are further compounded by a third one, namely that the remarkable process of writing our Constitution, and the meaning of the document, is little known both in South Africa and abroad.

On a personal level, understanding this profoundly inspiring story has been a once in a lifetime opportunity to gain perspective on a history that one of us was too young to experience and which another had lived through but had not fully processed. The nail-biting moments and the immense will of arch-enemies to overcome their hatred provides us with courage for facing difficulties in our own lives. It is inspirational precisely because it is not a story of a triumphant ending. This is a story of collective struggle, grit, clawing ourselves back from the brink of disaster, and importantly it provides us with a template for confronting our inner struggles. Our founding story reminds South Africans of how practiced we are at transforming despair into hope.

Few know of the cut-and-thrust of the negotiations that ended apartheid, the fierce debates that shaped specific paragraphs of the Constitution and the behind-the-scenes challenges that were overcome to enable a transition from tyrannical rule to a constitutional democracy. Our exhibition tells these stories by drawing from archival material about the process; by seeking multiple voices from those involved from different political parties; and by creating multimedia resources that convey the process in a highly accessible manner.

This is a story of collective struggle, grit, clawing ourselves back from the brink of disaster, and importantly it provides us with a template for confronting our inner struggles.

There was something transformative about discovering the nitty-gritties of the story and exploring the pressing questions during the negotiations for a free South Africa: Should we have three rotating presidents representing different ethnic groups and governing by consensus? How could we avert an all-out war when armed white right-wing extremists joined political forces with homeland leaders in a common threat to derail the first democratic elections in 1994?

What is astounding about this story is how little is generally known of the Constitution’s deep African roots. In 1923 the ANC produced its first Bill of Rights, a document that is the precursor to our much-lauded Constitutional Bill of Rights. In 1943, the ANC expanded on these rights in its African Claims document which was followed by the Freedom Charter in 1955. Many South Africans do not know of our long contribution to the global human rights movement. The accessibility of this history will do much to engender the Constitution in our lives as an African document.

Unfortunately, the invisibility of women as role players in narratives of struggles for democracy has created a limited and patriarchal sense of history. Our virtual exhibition deliberately redresses the exclusion of women. We uncover the stories of little-known women leaders across all races such as Princess Emma, Nokutela Dube, Josie Palmer Mpama, Ray Alexander Simons and Francis Goitsemang Baard. Women in our history of the liberation struggle are often portrayed as the ‘wives or mothers of’ their male counterparts rather than as leaders in their own rights. Apartheid distorted and excluded the histories of the majority in South Africa from our greater historical narrative. The act of centering women in our history–leaders with agency both in local communities and on the world stage–is an important act to reclaim an untold story. We hope it contributes to repositioning women in our society where misogyny is still commonplace.

The process of building the virtual exhibition included diverse voices and contributors with a host of different skills ranging from a former Constitutional Court judge to legal experts and historians, to graphic design and web development specialists. The team journeyed to museums and archives around the world to imbibe best practices in creating an enticing visitor experience. We formed creative relationships with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, as well as with Local Projects, a New York museum design company. Importantly, we created partnerships with local organizations in South Africato ensure that we worked with the same unifying spirit that defined the constitution-making process.

Our work took on a new depth after extensive visits to the National Archive and Records Services of South Africa (NARSSA) in Pretoria. Together with a group of political science students, who had never visited an archive before, we delved into the hundreds of dusty boxes containing precious material. The documents revealed the mindsets behind the respective bargaining positions during the constitutional negotiations. The students walked away engaged with the immense power of the archive and its important role in the telling of history–our history. We have now finished the process of digitizing over 220,000 documents that make up the founding collections of our democracy. These digital files are being processed and will soon be available on the virtual exhibition. Accessibility to this archive will allow students, researchers and the public at large to easily use this rich resource to inform their work, further amplifying this seminal history.

Through this virtual exhibition we hope that our audience realizes that we all have a huge obligation as citizens to add our voices to this story to ensure a more nuanced and representative history and ultimately to ensure a future founded on common ground.